Oleanolsäure

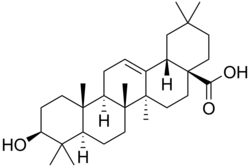

| Strukturformel | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Allgemeines | |||||||||||||||||||

| Name | Oleanolsäure | ||||||||||||||||||

| Andere Namen | |||||||||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C30H48O3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Externe Identifikatoren/Datenbanken | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Eigenschaften | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 456,71 g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aggregatzustand |

fest | ||||||||||||||||||

| Schmelzpunkt | |||||||||||||||||||

| Löslichkeit |

nahezu unlöslich in Wasser, gut löslich in Methanol[2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sicherheitshinweise | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Toxikologische Daten | |||||||||||||||||||

| Soweit möglich und gebräuchlich, werden SI-Einheiten verwendet. Wenn nicht anders vermerkt, gelten die angegebenen Daten bei Standardbedingungen (0 °C, 1000 hPa). | |||||||||||||||||||

Oleanolsäure ist ein pentacyclisches Triterpen, das aus fünf Cyclohexanringen aufgebaut ist. Das Sapogenin Oleanolsäure ist ein natürlicher Bestandteil einer Reihe von Pflanzen.

Vorkommen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Oleanolsäure ist als Naturstoff in einer Vielzahl von Pflanzen enthalten. Beispielsweise kann sie aus Salbei (Salvia officinalis), Rosmarin (Salvia rosmarinus)[4], Gemeinem Efeu (Hedera helix),[5] Zuckerrüben (Beta vulgaris), Ginseng (Panax ginseng), Breitwegerich (Plantago major), Syzygium cumini, Pistazien (Pistazia vera), Trester von Oliven (Olea europaea)[6] besonders konzentriert und Weißbeerigen Misteln (Viscum album)[7] gewonnen werden.

Pharmakologische Eigenschaften

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Oleanolsäure ist schwach zytotoxisch und weist nur ein geringes anti-oxidatives Potenzial auf. Da die pharmakologisch interessanten Eigenschaften nur relativ schwach ausgeprägt sind, wurden verschiedene Derivate der Oleanolsäure hergestellt, die eine erheblich höhere Potenz haben.[8] Ein Derivat mit deutlich höherem Potenzial ist Bardoxolon (2-Cyan-3,12-dioxo-l,9-dien-28-oleanolsäure, CDDO), beziehungsweise dessen Methylester (Bardoxolon-Methyl). Bardoxolon ist eine vielversprechende chemopräventive und zytostatische Substanz, die anti-proliferativ und pro-apoptotisch wirkt.[9] Die Verbindung befindet sich in der klinischen Erprobung (Phase I/II).[10][11] Zur Behandlung von chronischer Niereninsuffizienz ist Bardoxolon-Methyl in der klinischen Phase III.[12]

Seit 1977 wird Oleanolsäure in China und Japan bei Lebererkrankungen als orales Therapeutikum verwendet. Seit 1986 gegen Hyperlipidämie und nichtlymphatische Leukämie. In Japan ist seit 1990 eine oleanolhaltige Creme zum Schutz vor Hautkrebs im Handel.[6]

Siehe auch

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Weiterführende Literatur

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- A. Bishayee, S. Ahmed, N. Brankov, M. Perloff: Triterpenoids as potential agents for the chemoprevention and therapy of breast cancer. In: Frontiers in bioscience Band 16, 2011, S. 980–996, PMID 21196213. PMC 3057757 (freier Volltext). (Review).

- M. B. Sporn, K. T. Liby, M. M. Yore, L. Fu, J. M. Lopchuk, G. W. Gribble: New synthetic triterpenoids: potent agents for prevention and treatment of tissue injury caused by inflammatory and oxidative stress. In: Journal of Natural Products Band 74, Nummer 3, März 2011, S. 537–545, doi:10.1021/np100826q. PMID 21309592. PMC 3064114 (freier Volltext). (Review).

- J. L. Ríos: Effects of triterpenes on the immune system. In: Journal of ethnopharmacology Band 128, Nummer 1, März 2010, S. 1–14, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.045. PMID 20079412. (Review).

- I. Sogno, N. Vannini, G. Lorusso, R. Cammarota, D. M. Noonan, L. Generoso, M. B. Sporn, A. Albini: Anti-angiogenic activity of a novel class of chemopreventive compounds: oleanic acid terpenoids. In: Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progrès dans les recherches sur le cancer Band 181, 2009, S. 209–212, PMID 19213570. (Review).

- A. Petronelli, G. Pannitteri, U. Testa: Triterpenoids as new promising anticancer drugs. In: Anti-Cancer Drugs Band 20, Nummer 10, November 2009, S. 880–892, doi:10.1097/CAD.0b013e328330fd90. PMID 19745720. (Review).

- M. N. Laszczyk: Pentacyclic triterpenes of the lupane, oleanane and ursane group as tools in cancer therapy. In: Planta Medica Band 75, Nummer 15, Dezember 2009, S. 1549–1560, doi:10.1055/s-0029-1186102. PMID 19742422. (Review).

- B. Yu, J. Sun: Current synthesis of triterpene saponins. In: Chemistry, an Asian journal Band 4, Nummer 5, Mai 2009, S. 642–654, doi:10.1002/asia.200800462. PMID 19294723. (Review).

- N. Sultana, A. Ata: Oleanolic acid and related derivatives as medicinally important compounds. In: Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry Band 23, Nummer 6, Dezember 2008, S. 739–756, doi:10.1080/14756360701633187. PMID 18618318.

- J. Liu: Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid: research perspectives. In: Journal of ethnopharmacology Band 100, Nummer 1–2, August 2005, S. 92–94, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.024. PMID 15994040. (Review).

- Z. Ovesná, A. Vachálková, K. Horváthová, D. Tóthová: Pentacyclic triterpenoic acids: new chemoprotective compounds. Minireview. In: Neoplasma Band 51, Nummer 5, 2004, S. 327–333, PMID 15640935. (Review).

Einzelnachweise

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ Eintrag zu OLEANOLIC ACID in der CosIng-Datenbank der EU-Kommission, abgerufen am 18. Mai 2020.

- ↑ a b T. Mühle: Trennung der Positionsisomere Oleanolsäure und Ursolsäure. Diplomica Verlag, 2009, ISBN 3-836-67870-5, S. 7 (eingeschränkte Vorschau in der Google-Buchsuche).

- ↑ a b c Datenblatt Oleanolic acid bei Sigma-Aldrich, abgerufen am 24. April 2011 (PDF).

- ↑ Dr. P.N. Ravindran: The Encyclopedia of Herbs and Spices (Inhaltsstoffe, Triterpene in der Arzneidroge) In: Google Books, 2017, S. 812.

- ↑ Salbei konzentriert – Wirkstoff der alten Heilpflanze effektiv gewinnen. (Seite dauerhaft nicht mehr abrufbar, festgestellt im Mai 2019. Suche in Webarchiven) (PDF; 851 kB) Fachhochschule Münster, S. 26–27.

- ↑ a b H. Schmandke: Triterpenoide in Oliven. (PDF; 283 kB) In: Ernährungs Umschau 2, 2009, S. 92–95.

- ↑ S. Jäger, A. Scheffler, H. Schmellenkamp: Pharmakologie ausgewählter Terpene. In: Pharmazeutische Zeitung 22, 2006.

- ↑ A. Bishayee, S. Ahmed, N. Brankov, M. Perloff: Triterpenoids as potential agents for the chemoprevention and therapy of breast cancer. In: Frontiers in bioscience Band 16, 2011, S. 980–996, PMID 21196213. PMC 3057757 (freier Volltext). (Review).

- ↑ D. Deeb, X. Gao, Y. Liu, D. Jiang, G. W. Divine, A. S. Arbab, S. A. Dulchavsky, S. C. Gautam: Synthetic triterpenoid CDDO prevents the progression and metastasis of prostate cancer in TRAMP mice by inhibiting survival signaling. In: Carcinogenesis Band 32, Nummer 5, Mai 2011, S. 757–764, doi:10.1093/carcin/bgr030. PMID 21325633. PMC 3086702 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Klinische Studie (Phase I/II): CDDO in Treating Patients With Metastatic or Unresectable Solid Tumors or Lymphoma bei Clinicaltrials.gov der NIH

- ↑ A. Petronelli, E. Pelosi, S. Santoro, E. Saulle, A. M. Cerio, G. Mariani, C. Labbaye, U. Testa: CDDO-Im is a stimulator of megakaryocytic differentiation. In: Leukemia Research Band 35, Nummer 4, April 2011, S. 534–544, doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2010.09.013. PMID 21035854.

- ↑ Klinische Studie (Phase III): Bardoxolone Methyl Evaluation in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes (BEACON) bei Clinicaltrials.gov der NIH

Weblinks

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- Pharmakologie ausgewählter Terpene. Pharmazeutische Zeitung