Benutzer:Autokrator/Spätrömische Armee

Spätrömische Armee ist der Begriff, der für die Streitkräfte des Römischen Reiches von der Thronbesteigung des Diokletian im Jahr 284 n. Chr. bis zur entgültigen Teilung des Reiches in eine westliche und östliche Hälfte im Jahr 395 verwendet wird. Wenige Jahrzehnte später löste sich die weströmische Armee im Zuge des Zusammenbruchs des Westreiches auf. Die Oströmische Armee existierte weiterhin intakt und insgesamt unverändert bis zur Schaffung der Themen im 7. Jahrhundert. Der Begriff "Spätrömische Armee" wird oft gebraucht um die Oströmische Armee miteinzubeziehen.

Überblick

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Die Armee des Prinzipats war infolge der Erschütterungen des 3. Jahrhunderts tiefgreifenden Veränderungen unterworfen. Anders als die Armee des Prinzipats war die Armee des 4. Jahrhunderts in hohem Maße von Konskription abhängig und die Soldaten wurden bei weitem geringer entlohnt als im 2. Jahrhundert. Barbaren von außerhalb der Reichsgranzen stellten wahrscheinlich einen viel höheren Anteil an der Gesamtstärke des Heeres als in den beiden Jahrhunderten zuvor, es gibt aber keine Hinweise darauf, dass dies die Schlagkraft des Heeres verminderte.

Die Armee des 4. Jahrhunderts war wahrscheinlich nicht bedeutend größer als die des 2. Jahrhunderts. Der fundamentalste Wandel war das Schaffen großer Armeen, die den Kaiser begleiteten (comitatus praesentales) und somit nicht in der Grenzverteidigung eingesetzt wurden. Ihr Hauptzweck war es, Usurpationen zu verhindern. Die Legionen wurden in kleinere Verbände aufgeteilt, in der Größe mit den Auxiliartruppen des Prinzipats. Parallel dazu wurde Legionärsbewaffnung und -Ausrüstungzugunsten von Auxilia-ähnlicher Ausrüstung aufgegeben. Infanterie wurde mit den schwereren Rüstungen der römischen Kavallerie des Prinzipats ausgerüstet.

Die Rolle der Kavallerie scheint sich im Vergleich zur Armee des Prinzipats nicht besonders erweitert zu haben. Es scheint, als habe Kavallerie einen ähnlichen Anteil am Gesamtheer gestellt wie im 2. Jahrhundert und auch ihre taktische Rolle beibehalten habe. Tatsächlich gelangte die wegen ihrer Rolle in drei großen Schlachten des 4. Jahrhunderts zu einem Ruf von Inkompetenz und Feigheit. Im Gegensatz dazu behielt die Kavallerie ihren traditionell exzellenten Ruf.

Im 3. und 4. Jahrhundert wurden viele existierende Grenzenfestungen ausgebaut um sie leichter verteidigen zu können sowie das Erbauen neuer Befestigungen mit viel größerem defensivem Potenzial. Dieses Verhalten hat in der Fachwelt zu Kontroversen geführt, ob die Römer einer verzögernden Verteidigungsstrategie fanden oder ihre Taktik der "Vorwärtsverteidigung" aus der Zeit des frühen Prinzipats behielten, beispielsweise die exponierte Stellung von Kastellen, häufige militärische Operationen beiderseits der römischen Grenze sowie Pufferzonen aus verbündeten Stämmen. Wie auch immer die Verteidigungsstrategie geartet war, sie war offensichtlich weniger erfolgreich als im 1. und 2. Jahrhundert. Dies könnte an verstärktem Druck der Barbaren gelegen haben und/oder an der Praxis, die schlagkräftigsten Truppen im Inneren des Reiches zu stationieren und die Grenztruppen wertvoller Verstärkung zu berauben.

Quellen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

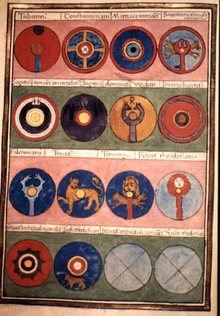

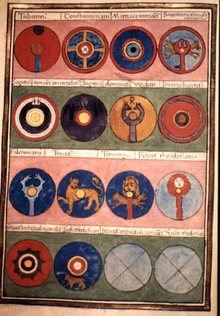

Ein Gutteil der Informationen, die uns zur römischen Armee des 4. Jahrhunderts zur Verfügung stehen, befindet sich in einem einzigen Dokument, bekannt als Notitia Dignitatum (zusammengestellt ca. 395–420). Sie ist ein Handbuch aller spätrömischen Ämter, militärisch und zivil. Das Hauptproblem der Notitia als Quelle ist das völlige Fehlen jeglicher Angaben zu den Mannschaftsstärken, was eine Einschätzung der Armeegröße unmöglich macht. Auch wurde das unmittelbar vor Ende des 4. Jahrhunderts zusammengestellt, es ist also schwierig Schätzungen über den Zustand der Armee davor zu machen. Wegen Ermangelung anderer Quellen bleibt die Notitia die Hauptquelle zur spätrömischen Armee.[1] Die Notitia weist zahlreiche Lacunae und Fehler auf, bedingt durch jahrhundertelanges Kopieren.

Die wichtigste schriftliche Quelle zum 4. Jahrhundert sind die Res Gestae (Taten) des Ammianus Marcellinus, dessen Bücher die Periode von 353 bis 378 behandeln. Marcellinus, selbst ein Veteran, wird von Fachleuten als verlässliche Quelle angesehen. Seine Werke können aber auch keine Erhellung in die Unklarheiten in der Notitia bezüglich Armee- und Einheitsstärken oder Gesamtzahl der Einheiten bringen, da er diese Themen nur selten im Detail behandelt. Die dritte große Quelle zur spätrömischen Armee sind die Codizes, die im 5. und 6. Jahrhundert im Oströmischen Reich herausgegeben wurden: Der Codex Theodosianus (438) und der Corpus Iuris Civilis (528–39). Diese Zusammenstellungen römischen Rechts aus enhalten zahlreiche kaiserliche Dekrete bezüglich der Verwaltung der Armee.

De re militari, ein Traktat des Vegetius zu römischem Heereswesen, enthält wichtige Informationen zur spätrömischen Armee, obwohl sein Fokus auf den Armeen der Republik und des Prinzipats liegt. Aber Vegetius (der keine militärische Erfahrung besaß) ist oft unverlässlich. Zum Beispiel versichert er, die römische Armee habe Rüstungen und Helme im 4. Jahrhundert aufgegeben (mit der absurden Begründung, diese seien zu schwer gewesen), was durch bildhauerische und künstlerischen Arbeiten widerlegt werden kann.[2] Generell ist es nicht anzuraten, einer Aussage von Vegetius vorbehaltlos zu vertrauen.

Die Erforschung der spätrömischen Armee muss sich mit dem im Verlauf des 3. und 4. Jahrhunderts feststellbaren Abfallen epigraphischen Materials verglichen mit den ersten beiden nachchristlichen Jahrhunderten auseinandersetzen. Römische Militärdiplome wurden nach 203 nicht mehr an ausgeschiedene Auxiliare vergeben (wahrscheinlich waren sie zu diesem Zeitpunkt bereits fast alle römische Bürger). Außerdem gab es eine starke Verringerung von militärischen Grabsteinen und Altären. Offizielle Stempel römischer Einheiten an Gebäuden (z.B. Dachziegeln) wurden rarer. Dieser Trend sollte dennoch nicht als Verlust der hohen Entwicklungsstufe im römischen Militärwesen gesehen werden. Papyrusfunde aus Ägypten beweisen, dass militärische Verbände im 4. Jahrhundert weiterhin detaillierte Aufzeichnungen abfassten, welche größtenteils verloren sind. Der Niedergang epigraphisch verfasster Inschriften ist wahrscheinlich auf veränderte Vorlieben zurückzuführen, die vom steigenden Anteil barbarischer Rekruten sowie dem Aufstieg des Christentums zurückzuführen ist.[3]

Evolution der Armee im 4. Jahrhundert

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Hintergrund: die Armee im Prinzipat

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The regular army of the Principate was established by the founder–emperor Augustus (ruled 30 BC – 14 AD) and survived until the end of the 3rd century. The regular army consisted of two distinct corps, both being made up of mainly volunteer professionals.

The elite legions were large infantry formations, varying between 25 and 33 in number, of ca. 5,500 men each (all infantry save a small cavalry arm of 120) which admitted only Roman citizens.[4] The auxilia consisted of around 400 much smaller units of ca. 500 men each (a minority were up to 1,000 strong), which were divided into approximately 100 cavalry alae, 100 infantry cohortes and 200 mixed cavalry/infantry units or cohortes equitatae.[5] Some auxilia regiments were designated sagittariorum, meaning that they specialised in archery. The auxilia thus contained almost all the Roman army's cavalry and archers, as well as (from the late 1st century onwards) approximately the same number of foot soldiers as the legions.[6] The auxilia were mainly recruited from the peregrini: provincial subjects of the empire who did not hold Roman citizenship, but the auxilia also admitted Roman citizens and possibly barbari, the Roman term for peoples living outside the empire's borders.[7] At this time both legions and auxilia were almost all based in frontier provinces.[8] The only substantial military force at the immediate disposal of the emperor was the elite Praetorian Guard of 10,000 men which was based in Rome.[9]

The senior officers of the army were, until the 3rd century, mainly from the Italian aristocracy. This was divided into two orders, the senatorial order (ordo senatorius), consisting of the ca. 600 sitting members of the Roman Senate and their sons and grandsons, and the more numerous (several thousand-strong) equites or "knights".

Hereditary senators and equites combined military service with civilian posts, a career path known as the cursus honorum, typically starting with a period of junior administrative posts in Rome, followed by 5–10 years in the military and a final period of senior positions in the either the provinces or Rome.[10] This tiny, tightly-knit ruling oligarchy of under 10,000 men monopolised political, military and economic power in an empire of ca. 80 million inhabitants and achieved a remarkable degree of political stability. During the first 200 years of its existence (30 BC – 180 AD), the empire suffered only one major episode of civil strife (the Civil War of 68–9). Otherwise, usurpation attempts by provincial governors were few and swiftly suppressed.

As regards the military, members of the senatorial order (senatorii) exclusively filled the following posts:

- (a) legatus Augusti pro praetore (provincial governor of a border province, who was commander-in-chief of the military forces deployed there as well as heading the civil administration)

- (b) legatus legionis (legion commander)

- (c) tribunus militum laticlavius (legion deputy commander).[11]

The equites provided:

- (a) the governors (procuratores) of Egypt and of a few minor provinces

- (b) the two praefecti praetorio (commanders of the Praetorian Guard)

- (c) a legion's praefectus castrorum (3rd-in-command) and its remaining five tribuni militum (senior staff officers)

- (d) the praefecti (commanders) of the auxiliary regiments.[12]

By the late 1st century, a distinct equestrian group, non-Italian and military in character, became established. This was a result of the established custom whereby the emperor elevated the primuspilus (chief centurion) of each legion to equestrian rank on completion of his year in office. This resulted in some 30 career soldiers, mostly non-Italian and risen from the ranks, joining the aristocracy each year.[13] Far less wealthy than their Italian counterparts, many such equites belonged to families that provided career soldiers for generations. Prominent among them were Romanised Illyrians, the descendants of the Illyrian-speaking tribes that inhabited the Roman provinces of Pannonia (W Hungary/Slovenia), Dalmatia (Croatia/Bosnia) and Moesia Superior (Serbia), together with the neighbouring Thracians of Moesia Inferior (N Bulgaria) and Macedonia provinces. From the time of Domitian (ruled 81–96), when over half the Roman army was deployed in the Danubian regions, the Illyrian and Thracian provinces became the most important recruiting ground of the auxilia and later the legions.[14]

Entwicklungen im 3. Jahrhundert

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The seminal development for the army in the early 3rd century was the Constitutio Antoniniana (Antonine Decree) of 212, issued by Emperor Caracalla (ruled 211–18). This granted Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire, ending the second-class status of the peregrini.[16] This had the effect of breaking down the distinction between the citizen legions and the auxiliary regiments. In the 1st and 2nd centuries, the legions were the symbol (and guarantors) of the dominance of the Italian "master nation" over its subject peoples. In the 3rd century, they were no longer socially superior to their auxiliary counterparts (although they may have retained their elite status in military terms) and the legions' special armour and equipment (e.g. the lorica segmentata) was phased out.[17]

The traditional alternation between senior civilian and military posts fell into disuse in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, as the Italian hereditary aristocracy was progressively replaced in the senior echelons of the army by the primipilares (former chief centurions).[18] In the 3rd century, only 10% of auxiliary prefects whose origins are known were Italian equestrians, compared to the majority in the previous two centuries.[19] At the same time, equestrians increasingly replaced the senatorial order in the top commands. Septimius Severus (ruled 197–211) placed equestrian primipilares in command of the three new legions he raised and Gallienus (260–68) did the same for all the other legions, giving them the title praefectus pro legato ("prefect acting as legate").[20][21] The rise of the primipilares may have provided the army with more professional leadership, but it increased military rebellions by ambitious generals. The 3rd century saw numerous coups d'état and civil wars. Few 3rd-century emperors enjoyed long reigns or died of natural causes.[22]

Emperors responded to the increased insecurity with a steady build-up of the forces at their immediate disposal. These became known as the comitatus ("escort", from which derives the English word "committee"). To the Praetorian Guard's 10,000 men, Septimius Severus added the legion II Parthica. Based at Albano Laziale near Rome, it was the first legion to be stationed in Italy since Augustus. He doubled the size of the imperial escort cavalry, the equites singulares Augusti, to 2,000 by drawing select detachments from alae on the borders.[23] His comitatus thus numbered some 17,000 men, equivalent to 31 infantry cohortes and 11 alae of cavalry.[24] The trend for the emperor to gather round his person ever greater forces reached its peak in the 4th century under Constantine I the Great (ruled 312–37) whose comitatus may have reached 100,000 men, perhaps a quarter of the army's total effective strength.[25]

The rule of Gallienus saw the appointment of a senior officer, with the title of dux (plural form: duces, the origin of the medieval noble rank of duke), to command all the comitatus cavalry. This force included equites promoti (cavalry contingents detached from the legions), plus Illyrian light cavalry (equites Dalmatarum) and allied barbarian cavalry (equites foederati).[21] Under Constantine I, the head of the comitatus cavalry was given the title of magister equitum ("master of horse"), which in Republican times had been held by the deputy to a Roman dictator.[26] But neither title implies the existence of an independent "cavalry army", as was suggested by some more dated scholars. The cavalry under both officers were integral to mixed infantry and cavalry comitatus, with the infantry remaining the predominant element.[24]

The 3rd century saw a progressive reduction in the size of the legions and even some auxiliary units. Legions were broken up into smaller units, as evidenced by the shrinkage and eventual abandonment of their traditional large bases, documented for example in Britain.[27] In addition, from the 2nd century onwards, the separation of some detachments from their parent units became permanent in some cases, establishing new unit types, e.g. the vexillatio equitum Illyricorum based in Dacia in the early 2nd century[28] and the equites promoti[21] and numerus Hnaufridi in Britain.[29] This led to the proliferation of unit types in the 4th century, generally of smaller size than those of the Principate. For example, in the 2nd century, vexillatio (from vexillum = "standard") was a generic term meaning any detachment from a legion or auxiliary regiment, either cavalry or infantry. In the 4th century, it denoted an elite cavalry regiment.[30]

From the 3rd century are the first records of a small number of regular units bearing the names of barbarian tribes (as opposed to peregrini tribal names). These were foederati (allied troops under a military obligation to Rome) converted into regular units, a trend that was to accelerate in the 4th century.[31] The ala I Sarmatarum, based in Britain, was probably composed of some of the 5,500 captured Sarmatian horsemen sent to garrison Hadrian's Wall by emperor Marcus Aurelius in ca. 175.[32] There is no evidence of irregular barbarian units becoming part of the regular Principate army until the 3rd century.[33]

Reichskrise des 3. Jahrhunderts

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The mid-3rd century saw the empire plunged into a military and economic crisis which almost resulted in its disintegration. It consisted of a series of military catastrophes in 251–271 when Gaul, the Alpine regions and Italy, the Balkans and the East were overrun by Alamanni, Sarmatians, Goths and Persians.[34] At the same time, the Roman army was struggling with the effects of a devastating pandemic, now thought to have been smallpox, the Plague of Cyprian which began in 251 and was still raging in 270, when it claimed the life of Emperor Claudius II Gothicus (268–70).[35] The evidence for the earlier Antonine pandemic of the late 2nd century, probably also smallpox, indicates a mortality of 15–30% in the empire as a whole.[36] Zosimus describes the Cyprianic outbreak as even worse.[37] The armies and, by extension, the frontier provinces where they were based (and mainly recruited), would likely have suffered deaths at the top end of the range, due to their close concentration of individuals and frequent movements across the empire.[38]

The 3rd-century crisis started a chain-reaction of socio-economic effects that proved decisive for the development of the late army. The combination of barbarian devastation and reduced tax-base due to plague bankrupted the imperial government, which resorted to issuing ever more debased coin e.g. the antoninianus, the silver coin used to pay the troops in this period, lost 95% of its silver content between its launch in 215 and its demise in the 260s. Thus 20 times more money could be distributed with the same amount of precious metal.[39] This led to rampant price inflation: for example, the price of wheat under Diocletian was 67 times the typical Principate figure.[40] The monetary economy collapsed and the army was obliged to rely on unpaid food levies to obtain supplies.[41] Food levies were raised without regard to fairness, ruining the border provinces where the military was mainly based.[42] Soldiers' salaries became worthless, which reduced the army's recruits to a subsistence-level existence.[43] This in turn discouraged volunteers and forced the government to rely on conscription[44] and large-scale recruitment of barbarians into the regular army because of the shortfalls caused by the plague. By the mid-4th century, barbarian-born men probably accounted for about a quarter of all recruits (and over a third in elite regiments), likely a far higher share than in the 1st–2nd centuries.[45]

Illyrische Militärdiktatur

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

By the 3rd century, Romanised Illyrians and Thracians, mostly primipilares and their descendants, came to dominate the army's senior officer echelons.[46] Finally, the Illyrian/Thracian officer class seized control of the state itself. In 268, the emperor Gallienus (ruled 260–68) was overthrown by a coup d'état organised by a clique of Illyrian senior officers, including his successors Claudius II Gothicus and Aurelian (270–75).[47] They and their successors Probus (276–82) and Diocletian (ruled 284–305) and his colleagues in the Tetrarchy formed a sort of self-perpetuating military junta of Illyrian officers who were born in the same provinces (several in the same city, Sirmium, a major legionary base in Moesia Superior) or had served in the same regiments.[14]

The junta reversed the military disasters of 251–71 with a string of victories, most notably the defeat at Naissus of a vast Gothic army by Claudius II, which was so crushing that the Goths did not seriously threaten the empire again until a century later at Adrianople (378).[48]

The Illyrian emperors were especially concerned with the depopulation of the border provinces due to plague and barbarian invasions during the Crisis. The problem was especially acute in their own Danubian home provinces, where much arable land had fallen out of cultivation through lack of manpower.[49] The depopulation was thus a serious threat to army recruitment and supply. In response, the Illyrian junta pursued an aggressive policy of resettling defeated barbarian tribesmen on imperial territory on a massive scale. Aurelian moved a large number of Carpi to Pannonia in 272.[50] (In addition, by 275 he evacuated the province of Dacia, removing the entire provincial population to Moesia, an act largely motivated by the same problem).[51] His successor Probus is recorded as transferring 100,000 Bastarnae to Moesia in 279/80 and later equivalent numbers of Gepids, Goths and Sarmatians.[52] Diocletian continued the policy, transferring in 297 huge numbers of Bastarnae, Sarmatians and Carpi (the entire latter tribe, according to Victor).[50][53] Although the precise terms under which these people were settled in the empire are unknown (and may have varied), the common feature was the grant of land in return for an obligation of military service much heavier than the normal conscription quota. The policy had the triple benefit, from the Roman government's point of view, of weakening the hostile tribe, repopulating the plague-ravaged frontier provinces (and bringing their abandoned fields back into cultivation) and providing a pool of first-rate recruits for the army. But it could also be popular with the barbarian prisoners, who were often delighted by the prospect of a land grant within the empire. In the 4th century, such communities were known as laeti.[31]

The Illyrian emperors ruled the empire for over a century, until 379. Indeed, until 363, power was held by descendants of one of the original junta members. Constantine I' s father, Constantius Chlorus, was a Caesar (deputy emperor) in Diocletian's Tetrarchy.[54] His grandson Julian ruled until 363. The Illyrian emperors restored the army to its former strength and effectiveness, but were solely concerned with the needs and interests of the military. They were also divorced from the wealthy Roman senatorial families that dominated the Senate and owned much of the empire's land. This in turn bred a feeling of alienation from the army among the Roman aristocracy which in the later 4th century began to resist the military's exorbitant demands for recruits and supplies.[55]

Diokletian

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Diocletian is widely recognised as the greatest of the Illyrian emperors. Diocletian's wide-ranging administrative, economic and military reforms were aimed at providing the military with adequate manpower, supplies and military infrastructure.[56] In the words of one historian, "Diocletian ... turned the entire empire into a regimented logistic base" (to supply the army).[57]

Militärische Kommandostruktur

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Diocletian's administrative reforms had the twin aims of ensuring political stability and providing the bureaucratic infrastructure needed to raise the recruits and supplies needed by the army. At the top, Diocletian instituted the Tetrarchy. This divided the empire into two halves, East and West, each to be ruled by an Augustus (emperor). Each Augustus would in turn appoint a deputy called a Caesar, who would act both as his ruling partner (each Caesar was assigned a quarter of the empire) and designated successor. This four-man team would thus have the flexibility to deal with multiple and simultaneous challenges as well as providing for a legitimate succession.[58] The latter failed in its central aim, to prevent the disastrous civil wars caused by the multiple usurpations of the 3rd century . Indeed, the situation may have been made worse, by providing each pretender with a substantial comitatus to enforce his claim. Diocletian himself lived (in retirement) to see his successors fight each other for power. But the division of the empire into Eastern and Western halves, recognising both geographical and cultural realities, proved enduring: it was mostly retained during the 4th century and became permanent after 395.

Diocletian reformed the provincial administration, establishing a three-tiered provincial hierarchy, in place of the previous single-tier structure. The original 42 Principate provinces were almost tripled in number to ca. 120. These were grouped into 12 divisions called dioceses, each under a vicarius, in turn grouped into four praetorian prefectures, to correspond to the areas of command assigned to the four Tetrarchs, who were each assisted by a chief-of-staff called a praefectus praetorio (not be confused with the commanders of the Praetorian Guard, who held the same title). The aim of this fragmentation of provincial administration was probably to reduce the possibility of military rebellion by governors (by reducing the forces they each controlled).[59]

Also to this end, and to provide more professional military leadership, Diocletian started to divorce military from civil command at provincial level. Governors were stripped of command of the troops in their provinces in favour of purely military officers called duces limitis ("border commanders"). Some 20 duces may have been created under Diocletian.[49] Most duces were given command of forces in a single province, but a few controlled more than one province e.g. the dux Pannoniae I et Norici.[60] However, at higher echelons, military and administrative command remained united in the vicarii and praefecti praetorio.[59] In addition, Diocletian completed the exclusion of the senatorial class, still dominated by the Italian aristocracy, from all senior military commands and from all top administrative posts except in Italy.[61]

Heeresstärke

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]To ensure the army received sufficient recruits, Diocletian appears to have instituted systematic annual conscription of Roman citizens for the first time since the days of the Roman Republic. In addition, he was probably responsible for the decree, first recorded in 313, compelling the sons of serving soldiers and veterans to enlist.[44]

Under Diocletian, the number of legions, and probably of other units, more than doubled.[62] But it is unlikely that overall army size increased nearly as much, since unit strengths appear to have been reduced, in some cases drastically e.g. new legions raised by Diocletian appear to have numbered just 1,000 men, compared to the Principate establishment of ca. 5,500 i.e. the new legions increased overall legionary numbers by only ca. 15%.[63][64] Even so, scholars generally agree that Diocletian increased army numbers substantially, by at least 33%.[65] However, the only extant ancient figure for the size of Diocletian's army is 390,000, which is much the same as that of ca. 130 under Hadrian and well below the peak figure of 440,000 under Septimius Severus.[66][67] The apparent contradiction may be resolved if one accepts that Diocletian was starting from a much lower base than the Severus figure, as the army's effective size had probably shrunk sharply as a result of losses from plague and the military disasters of the late 3rd century.[68] In this case, simply restoring numbers to their 2nd-century level would have involved a major increase. (See Army size below).

Versorgung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Diocletian's primary concern was to place the provision of food supplies to the army on a rational and sustainable basis. To this end, the emperor put an end to the arbitrary exaction of food levies (indictiones) for the army, whose burden fell mainly on border provinces. He instituted a system of regular annual indictiones with the tax demanded set in advance for 5 years and related to the amount of cultivated land in each province, backed by a thorough empire-wide census of land, peasants and livestock.[69] To deal with the problem of rural depopulation (and consequent loss of food production), he decreed that peasants, who had always been free to leave their land during the Principate, must never leave the locality in which they were registered by the census. This measure had the effect of legally tying tenant farmers (coloni) and their descendants to their landlords' estates.[70]

Militärische Infrastruktur

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]In parallel with restoring the size of the army, Diocletian's efforts and resources were focused on a massive upgrading of the defensive infrastructure along all the empire's borders, including new forts and strategic military roads.[71] One of first steps to reforming the army was to reform the provinces in the Empire, creating militarized provinces towards the border which would act to protect, like a buffer zone, the unarmed provinces to the interior. As the threat along the borders became more sophisticated and powerful, the normal defence system of trying to fight the enemy on the exterior of the borders began to fail. The line of defence was kept along the frontier with stronger constructed walls as well as a stationary force.[72] Behind the walls any enemy who broke through would then find walled towns, forts and fortified farmhouses to restrict or slow down their advancement to give sufficient time for the mobile section of the army to fight the invasion.[73]

The structure of the army also changed. Instead of the auxiliary and legionary force, the new model was made up of mobile and stationed forces; the mobile force consisting of both cavalry and infantry, whereas the stationary force acted as a local militia. The cavalry section had unique fighting skills and would be able to fight unaccompanied, it became known as the vexilliatones.[74]

Konstantin

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

After defeating Maxentius in 312, Constantine disbanded the Praetorian Guard, ending the latter's 300-year existence.[75] Although the instant reason was the Guard's support for his rival Maxentius, a force based in Rome had also become obsolete since emperors now rarely resided there. The imperial escort role of the Guard's cavalry, the equites singulares Augusti, was now fulfilled by the scholae. These elite cavalry regiments existed by the time of Constantine and may have been founded by Diocletian.[76]

Constantine expanded his comitatus into a major and permanent force. This was achieved by the addition of units withdrawn from the frontier provinces and by creating new units: more cavalry vexillationes and new-style infantry units called auxilia. The expanded comitatus was now placed under the command of two new officers, a magister peditum to command the infantry and magister equitum for cavalry. Comitatus troops were now formally denoted comitatenses to distinguish them from the frontier forces (limitanei).[59] The size of the Constantinian comitatus is uncertain. But Constantine mobilised 98,000 troops for his war against Maxentius, according to Zosimus.[25] It is likely that most of these were retained for his comitatus.[26] This represented about a quarter of the total regular forces, if one accepts that the Constantinian army numbered around 400,000.[77] The rationale for such a large comitatus has been debated among scholars. A traditional view sees the comitatus as a strategic reserve which could be deployed against major barbarian invasions that succeeded in penetrating deep into the empire or as the core of large expeditionary forces sent across the borders. But more recent scholarship has viewed its primary function as insurance against potential usurpers.[24] (See Strategy of the Late Roman army below).

Constantine I completed the separation of military commands from the adminuistrative structure. The vicarii and praefecti praetorio lost their field commands and became purely administrative officials. However, they retained a crucial role in military affairs, as they remained responsible for military recruitment, pay and, above all, supply.[78] It is unclear whether the duces on the border now reported direct to the emperor, or to one of the two magistri of the comitatus.

In addition, Constantine appears to have reorganised the border forces along the Danube, replacing the old-style alae and cohortes with new units of cunei (cavalry) and auxilia (infantry) respectively.[59] It is unclear how the new-style units differed from the old-style ones, but those stationed on the border (as opposed to those in the comitatus) may have been smaller, perhaps half the size.[79] In sectors other than the Danube, old-style auxiliary regiments survived.[80]

The 5th-century historian Zosimus strongly criticised the establishment of the large comitatus, accusing Constantine of wrecking his predecessor Diocletian's work of strengthening the border defences: "By the foresight of Diocletian, the frontiers of the Roman empire were everywhere studded with cities and forts and towers... and the whole army was stationed along them, so it was impossible for the barbarians to break through... But Constantine ruined this defensive system by withdrawing the majority of the troops from the frontiers and stationing them in cities which did not require protection."[81] Zosimus' critique is probably excessive, both because the comitatus already existed in Diocletian's time and because some new regiments were raised by Constantine for his expanded comitatus, as well as incorporating existing units.[82] Nevertheless, the majority of his comitatus was drawn from existing frontier units.[63] This drawdown of large numbers of the best units inevitably increased the risk of successful large-scale barbarian breaches of the frontier defences.[83]

Spätes 4. Jahrhundert

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]On Constantine's death in 337, his three sons Constantine II, Constans and Constantius II, divided the empire between them, ruling the West (Gaul, Britain and Spain), the Centre (Italy, Africa and the Balkans), and the East respectively. They also each received a share of their father's comitatus. By 353, when only Constantius survived, it appears that the 3 comitatus had become permanently based in these regions, one each in Gaul, Illyricum and the East - Gaul and the East under a magister equitum, Illyricum under a comes (plural form: comites, from which derives the modern noble rank of count). By the 360s, the border duces reported to their regional comitatus commander.[75] However, in addition to the regional comitatus, Constantius retained a force that accompanied him everywhere, which was from then called a comitatus praesentalis (imperial escort army).[84] The three regional armies became steadily more numerous until, by the time of the Notitia (ca. 400), there were 6 in the West and 3 in the East.[59] These corresponded to the border dioceses of, in the West: Britannia, Tres Galliae, Illyricum (West), Africa and Hispaniae; and in the East: Illyricum (East), Thraciae and Oriens. Thus, the regional comitatus commander had become the military counterpart of the diocesan administrative head, the vicarius, in control of all military forces in the diocese, including the duces.[85][86] The evolution of regional comitatus was a partial reversal of Constantine's policy and, in effect, a vindication of Zosimus' critique that the limitanei had been left with insufficient support.[87]

Despite the proliferation of regional comitatus, the imperial escort armies remained in existence, and in the period of the Notitia (ca. 400) three comitatus praesentales, each 20–30,000 strong, still contained a total of ca. 75,000 men.[88] If one accepts that the army at the time numbered about 350,000 men, the escort armies still contained 20–25% of the total effectives. Regiments which remained with the escort armies were, not later than 365, denoted palatini (lit. "of the palace", from palatium), a higher grade of comitatenses.[84] Regiments were now classified in four grades, which denoted quality, prestige and pay. These were, in descending order, scholares, palatini, comitatenses and limitanei.[89]

Armeestärke

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The traditional view of scholars is that the 4th-century army was much larger than the 2nd century army, in the region of double the size. The late 6th-century writer Agathias, gives a global total of 645,000 effectives for the army "in the old days", presumed to mean at its peak under Constantine I.[90] This figure probably includes fleets, giving a total of ca. 600,000 for the army alone. A.H.M. Jones' Later Roman Empire (1964), which contains the fundamental study of the late Roman army, calculated a similar total of 600,000 (exc. fleets) by applying his own estimates of unit strength to the units listed in the Notitia Dignitatum.[91]

But the Agathias-Jones view has fallen out of favour with some historians in more recent times. Agathias' figure, if it has any validity at all, may represent the official, as opposed to actual, strength of the Constantinian army. In reality, the slim evidence is that late units were often severely under-strength, perhaps only about two-thirds of official.[92] Thus Agathias' 600,000 on paper may have been no more than ca. 400,000 in reality. The latter figure accords well with the other global figure from ancient sources, by the 6th century writer John Lydus, of 389,704 (excluding fleets) for the army of Diocletian. Lydus' figure is accorded greater credibility than Agathias' by scholars because of its precision (implying that it was found in an official document) and the fact that it is ascribed to a specific time period.[93]

Jones' figure of 600,000 is based on assumptions about limitanei unit strengths which may be too high. Jones calculated unit strengths in Egypt under Diocletian using papyrus evidence of unit payrolls. But a rigorous reassessment of the evidence by R. Duncan-Jones concluded that Jones had overestimated unit sizes by 2–6 times.[94] For example, Jones estimated legions on the frontiers at ca. 3,000 men and other units at ca. 500.[95] But Duncan-Jones' revisions found frontier legions of around 500 men, an ala of just 160 and an equites unit of 80. Even allowing for the possibility that some of these units were detachments from larger units, it is likely that Diocletianic unit strengths were far lower than earlier.[96]

Duncan-Jones' figures receive support from a substantial corpus of excavation evidence from all the imperial borders which suggests that late forts were designed to accommodate much smaller garrisons than their Principate predecessors. Where such sites can be identified with forts listed in the Notitia, the implication is that the resident units were also smaller. Examples include the Legio II Herculia, created by Diocletian, which occupied a fort just one-seventh the size of a typical Principate legionary base, implying a strength of ca. 750 men. At Abusina on the Rhine, the Cohors III Brittonum was housed in a fort only 10% the size of its old Trajanic fort, suggesting that it numbered only around 50 men. The evidence must be treated with caution as identification of archaeological sites with Notitia placenames is often tentative and again, the units in question may be detachments (the Notitia frequently shows the same unit in two or three different locations simultaneously). Nevertheless, the weight of the archaeological evidence favours small sizes for frontier units.[97]

At the same time, more recent work has suggested that the regular army of the 2nd century was considerably larger than the ca. 300,000 traditionally assumed. This is because the 2nd century auxilia were not just equal in numbers to the legions as in the early 1st century, but some 50% larger.[5] The Principate army probably reached a peak of nearly 450,000 (excluding fleets and foederati) at the end of the 2nd century.[67] Furthermore, the evidence is that the actual strength of 2nd century units was typically much closer to official (ca. 85%).[98] In any case, estimates of army strength for the Principate are based on much firmer evidence than those for the later period, which are highly speculative, as the table below shows.

| Army corps | Tiberius 24 |

Hadrian ca. 130 |

S. Severus 211 |

Reichskrise (3. Jahrhundert) ca. 270 |

Diokletian 284–305 |

Konstantin I end rule 337 |

Notitia ca. 420 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEGIONEN | 125,000[99] | 155,000[100] | 182,000[101] | ||||

| AUXILIA | 125,000[102] | 218,000[5] | 250,000[103] | ||||

| PRAETORIANERGARDE | ~~5,000[104] | ~10,000[105] | ~10,000 | ||||

| GESAMTSTÄRKE | 255,000[106] | 383,000[107] | 442,000[108] | 290,000?[109] | 390,000[66] | 410,000?[77] | 350,000?[110] |

NOTE: Nur die regulären Landstreitkräfte (ausgenommen irreguläre barbarische Foederati und Angehörige der Römischen Marine)

Armeestruktur

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The later 4th-century army contained three types of army group: (a) imperial escort armies (comitatus praesentales). These were ordinarily based near the imperial capitals (Milan in the West, Constantinople in the East), but usually accompanied the emperors on campaign. (b) Regional field armies (comitatus). These were based in strategic regions, on or near the frontiers. (c) Border armies (exercitus limitanei).[111]

Types (a) and (b) are both frequently defined as "mobile field armies". This is because, unlike the limitanei units, they were not based in fixed locations. But their strategic role was quite different. The escort armies' primary role was probably to provide the emperor's ultimate insurance against usurpers: the very existence of such a powerful force would deter many potential rivals, and if it did not, the escort army alone was often sufficient to defeat them.[24] Their secondary role was to accompany the emperor on major campaigns such as a foreign war or to repel a large barbarian invasion.[112] The regional comitatus, on the other hand, had the task of supporting the limitanei in operations in the region they were based in.[113]

Struktur des Führungsstabs

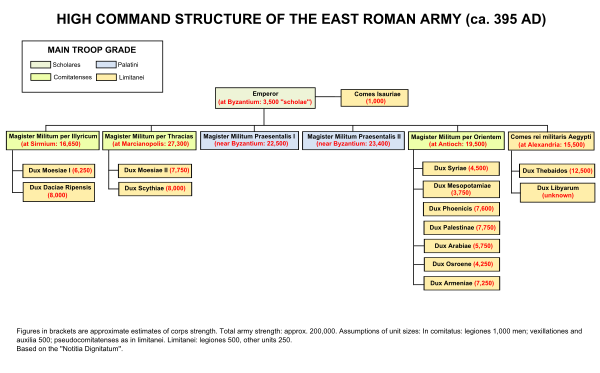

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Oströmisches Reich

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The eastern section of the Notitia is dated to ca. 395, at the death of Theodosius I. At this time, according to the Notitia, in the East there were 2 imperial escort armies (comitatus praesentales), each commanded by a magister militum praesentalis, the highest military rank, who reported direct to the emperor. These contained units of mainly palatini grade. In addition, there were 3 regional comitatus, in East Illyricum, Thraciae and Oriens dioceses, consisting mostly of comitatenses-grade troops. Each was commanded by a magister militum, who also reported direct to the emperor.[116]

An anomaly in the East is the existence of two corps of limitanei troops, in Egypt and Isauria, each commanded by a comes rei militaris, rather than a dux, who reported to the emperor direct, according to the Notitia.[116] However, imperial decrees of ca. 440 show that both these officers reported to the magister militum per Orientem.[86] One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the reporting arrangements changed between 395 and 440. By the latter date, if not earlier, the MM per Orientem had evidently become responsible for military forces in the whole of Oriens prefecture (which included Anatolia and Egypt) and not just the Oriens diocese.

The 13 eastern border duces are listed in the Notitia by the diocese in which their forces were deployed: (East) Illyricum (2 duces), Thraciae (2), Pontica (1), Oriens (6) and Aegyptum (2).[116] Jones and Elton argue that, from the 360's onwards, the duces reported to the commander of their diocesan comitatus: the magister militum per Illyricum, Thracias, Orientem and the comes per Aegyptum, respectively (on the basis of evidence in Ammianus for the period 353-78 and from 3 surviving imperial decrees dated 412, 438 and 440).[85][117][118] The dux Armeniae is shown under the Pontica diocese, whose military commander is not specified in the Notitia, but was probably the magister praesentalis II at the time of the Notitia.[119] Later, the dux Armeniae is likely to have come under the aegis of the magister militum per Orientem. The eastern structure as presented in the Notitia remained largely intact until the time of Justinian I (525-65).[86]

Weströmisches Reich

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The western section was completed considerably later than its eastern counterpart, ca. 425, after the West had been overrun by barbarian tribes.[120] However, it appears that the western section was compiled at various times, and several times revised, in the period ca. 400-25: e.g. the dispositions for Britain must date from before 410, as that is when Roman forces withdrew from Britain definitively.[115] This reflects the confusion of the times, with the dispositions of armies and commands constantly changing to reflect the needs of the moment e.g. the large comitatus in Spain, which was not a border diocese, but had in these years to contend with invasions of Visigoths, Suevi, Alans and Vandals. In consequence, the West section of the Notitia does not represent the western command structure as it stood in 395 (for which the eastern structure is a better guide). Also, whereas the eastern section represents a beginning (the essential structure of the East Roman army, which lasted at least ca. 550), the western section represents an army in crisis and close to its demise. The scale of the chaos in this period is illustrated by Heather's analysis of units in the army of the West. Of 181 comitatus regiments listed for 425, only 84 existed before 395; and many regiments in the comitatus were simply upgraded limitanei units, implying the destruction or dissolution of around 76 comitatus regiments during the period 395-425.[121] By 460, the western army had largely dissolved.

The western structure differed substantially from the eastern. In the West, the emperor was not in direct control of his regional comitatus chiefs, who instead reported to a military supremo, whose title is given in the Notitia as the magister peditum praesentalis (literally: "master of infantry in the emperor's presence"), but is known from other evidence to have usually held the equivalent title of magister utriusque militiae (abbreviation: MVM, literally "master of both services", i.e. of both cavalry and infantry). This officer was effectively the supreme commander of all western forces, in direct command, with a deputy named in the Notitia as magister equitum praesentalis, of the single but large western imperial escort army. Subordinate to the MVM were all the diocesan comitatus commanders in the West: Gaul, Britannia, Illyricum (West), Africa, Tingitania and Hispania. In contrast to their eastern counterparts, who all held magister militum rank, the commanders of the Western regional comitatus were all of the lower comes rank, save for the magister equitum per Gallias. This was presumably because all but the Gaul comitatus were smaller than the 20–30,000 typically commanded by a magister militum. This anomalous structure, with the emperor sidelined by a generalissimo, had arisen through the ascendancy of the half–Vandal military strongman Stilicho (395–408), who was appointed by Theodosius I as guardian of his infant son and successor Honorius. After Stilicho's death in 408, a succession of weak emperors ensured that this position continued, under Stilicho's successors (especially Aetius and Ricimer), until the dissolution of the Western empire in 476.[122]

According to the Notitia, all but two of the 12 Western duces also reported directly to the MVM and not to their regional comes.[115][123] However, this is out of line with the situation in the East and probably does not reflect the situation in 395 or indeed in 425. It would clearly have been an impractical arrangement, as the lack of an overall theatre commander would have rendered effective joint operations between comitatus and border armies impossible. The chaotic period 406-25 probably resulted in repeated ad hoc changes in reporting relationships to suit the needs of the moment. Faced with the confusing data of previous drafts, the final redactor of the Notitia presumably decided on the simple solution of showing all these officers as reporting directly to the MVM. However, a trace of the true organisation survives: the Notitia shows the duces of Caesariensis and Tripolitania as reporting to the comes Africae.[115] The western organisation chart here lists the duces under their respective diocesan senior officer, to reflect the likely position.[85] The only dux who is likely to have reported to the MVM direct was the dux Raetiae I et II, whose provinces belonged to the diocese of Italia.

Scholae

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]In both East and West, the scholae, the emperors' personal cavalry escort, lay outside the normal military chain of command. According to the Notitia, the tribuni (commanders) of the scholae reported to the magister officiorum, a senior civilian official.[124] However, this was probably for administrative purposes only. On campaign, a tribunus scholae probably reported direct to the emperor himself.[76]

Bases

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Comitatus troops and border troops had different accommodation arrangements. Most border units were based in forts as were their predecessors, the auxiliary regiments of the Principate (indeed, in many cases, the same forts).[125] Some of the larger limitanei units (legiones and vexillationes) were based in cities, probably in permanent barracks.[126]

Comitatus troops were also based in cities (when not on campaign: then they would be in temporary camps). But it seems that did not usually occupy purpose-built accommodation like the city-based limitanei. From the legal evidence, it seems they were normally compulsorily billeted in private houses (hospitalitas).[127] This is because they often wintered in different provinces. The comitatus praesentales accompanied their respective emperors on campaign, while even the regional comitatus would change their winter quarters according to operational requirements. However, in the 5th century, emperors rarely campaigned in person, so the praesentales became more static in their winter bases.[128] The Western comitatus praesentalis normally was based in and around Mediolanum (Milan) and the two Eastern comitatus in the vicinity of Constantinople.[128]

Regimente

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The changes to unit structure in the 4th century were reduction of unit sizes and increase in unit numbers, establishment of new unit types and establishment of a hierarchy of units more complex than the old one of legions and auxilia.[129]

Einheitengrößen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The evidence for the strength of late army units is very fragmented and equivocal.[130] The table below gives some recent estimates of unit strength, by unit type and grade:

| Cavalry unit type |

Comitatenses (inc. palatini) |

Limitanei | XXXXX | Infantry unit type |

Comitatenses (inc. palatini) |

Limitanei |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | 120–500 | Auxilium | 400–1,200 | |||

| Cuneus | 200–300 | Cohors | 160–500 | |||

| Equites | 80–300 | Legio | 800–1,200 | 500–1,000 | ||

| Schola* | 500 | Milites | 200–300 | |||

| Vexillatio | 400–600 | Numerus | 200–300 |

*Scholares were not technically comitatenses

Much uncertainty remains, especially regarding the size of limitanei regiments, as can be seen by the wide ranges of the size estimates. It is also possible, if not likely, that unit strengths changed over the course of the 4th century. For example, it appears that Valentinian I split about 150 comitatus units with his brother and co-emperor Valens. The resulting units may have been just half the strength of the parent units (unless a major recruitment drive was held to bring them all up to original strength).[130]

Scholae are believed to have numbered ca. 500 on the basis of a 6th century reference.[64]

In the comitatus, there is consensus that vexillationes were ca. 500 and legiones ca. 1,000 strong. The greatest uncertainty concerns the size of the crack auxilia palatina infantry regiments, originally formed by Constantine. The evidence is contradictory, suggesting that these units could have been either ca. 500 or ca. 1,000 strong, or somewhere in between.[132][133] If the higher figure were true, then there would be little to distinguish auxilia from legiones, which is the strongest argument in favour of ca. 500.

For the size of limitanei units, opinion is divided. Jones and Elton suggest from the scarce and ambiguous literary evidence that border legiones numbered ca. 1,000 men and that the other units contained in the region of 500 men each.[95][134] Others draw on papyrus and more recent archaeological evidence to argue that limitanei units probably averaged about half the Jones/Elton strength i.e. ca. 500 for legiones and around 250 for other units.[79][135]

Truppengattungen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Scholae

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Despite existing from the early 4th century, the only full list of scholae available is in the Notitia, which shows the position at the end of the 4th century/early 5th century. At that time, there were 12 scholae, of which 5 were assigned to the Western emperor and 7 to the Eastern. These regiments of imperial escort cavalry would have totalled ca. 6,000 men, compared to 2,000 equites singulares Augusti in the late 2nd century.[9] The great majority (10) of the scholae were "conventional" cavalry, armoured in a manner similar to the alae of the Principate, carrying the titles scutarii ("shield-men"), armaturae ("armour" or "harnesses") or gentiles ("natives"). These terms appear to have become purely honorific, although they may originally have denoted special equipment or ethnic composition (gentiles was a term used to describe barbarian tribesmen admitted to the empire on condition of military service). Only two scholae, both in the East, were specialised units: a schola of clibanarii (cataphracts, or heavily armoured cavalry), and a unit of mounted archers (sagittarii).[136][137] 40 select troops from the scholae, called candidati from their white uniforms, acted as the emperor's personal bodyguards.[76]

Comitatenses (inkl. palatini)

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]In the comitatus armies (both escort and regional) cavalry regiments were known as vexillationes, infantry regiments as either legiones or auxilia.[92] Auxilia were only graded as palatini, emphasising their elite status, while the legiones are graded either palatini or comitatenses.[115]

The majority of Roman cavalry regiments in the comitatus (61%) remained of the traditional semi-armoured type, similar in equipment and tactical role to the alae of the Principate and suitable for mêlée combat. These regiments carry a variety of titles: comites, equites scutarii, equites stablesiani or equites promoti. Again, these titles are probably purely traditional, and do not indicate different unit types or functions.[17] 24% of regiments were unarmoured light cavalry, denoted equites Dalmatae, Mauri or sagittarii (mounted archers), suitable for harassment and pursuit. Mauri light horse had served Rome as auxiliaries since the Second Punic War 500 years before. Equites Dalmatae, on the other hand, seem to have been regiments first raised in the 3rd century. 15% of comitatus cavalry regiments were heavily armoured cataphracti or clibanarii, which were suitable for the shock charge (all but one such squadrons are listed as comitatus regiments by the Notitia)[138]

Infantry regiments mostly fought in close order as did their Principate forebears. Infantry equipment was broadly similar to the that of auxiliaries in the 2nd century, with some modifications (see Equipment, below).[17]

Limitanei

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]In the limitanei forces, most types of regiment were present. For infantry, there are regiments called milites, numeri and auxilia as well as old-style legiones and cohortes. Cavalry regiments are called equites, cunei and old-style alae.[134]

The evidence is that comitatenses regiments were considered of higher quality than limitanei. But the difference should not be exaggerated. Suggestions have been made that the limitanei were a part-time militia of local farmers, of poor combat capability.[139] This view is rejected by many modern scholars.[134][140][141] The evidence is that limitanei were full-time professionals.[142] They were charged with combating the incessant small-scale barbarian raids that were the empire's enduring security problem.[143] It is therefore likely that their combat readiness and experience were high. This was demonstrated at the siege of Amida (359) where the besieged frontier legions resisted the Persians with great skill and tenacity.[144] Elton suggests that the lack of mention in the sources of barbarian incursions less than 400-strong implies that such were routinely dealt with by the border forces without the need of assistance from the comitatus.[145] Limitanei regiments often joined the comitatus for specific campaigns, and were sometimes retained by the comitatus long-term with the title of pseudocomitatenses, implying adequate combat capability.[142]

Spezialisten

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Vorlage:Externalimage The late Roman army contained a significant number of heavily armoured cavalry called cataphractarii (from the Greek kataphraktos, meaning "covered all over"). These were covered from neck to foot by scale and/or lamellar, and their horses were often armoured also. Cataphracts carried a long, heavy lance called a contus, ca. Vorlage:Convert long, that was held in both hands. Some also carried bows.[146] The central tactic of cataphracts was the shock charge, which aimed to break the enemy line by concentrating overwhelming force on a defined section of it. A type of cataphract called a clibanarius also appears in the 4th century record. This term may be derived from Greek klibanos (a bread oven) or from a Persian word. It is likely that clibanarius is simply an alternative term to cataphract, or it may have been a special type of cataphract.[17] This type of cavalry had been developed by the Iranic horse-based nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppes from the 6th-century BC onwards: the Scythians and their kinsmen the Sarmatians. The type was adopted by the Parthians in the 1st century BC and later by the Romans, who needed it to counter Parthians in the East and the Sarmatians along the Danube.[147] The first regiment of Roman cataphracts to appear in the archaeological record is the ala I Gallorum et Pannoniorum cataphractaria, attested in Pannonia in the early 2nd century.[148] Although Roman cataphracts were not new, they were far more numerous in the late army, with most regiments stationed in the East.[149]

Archer units are denoted in the Notitia by the term equites sagittarii (mounted archers) and sagittarii (foot archers, from sagitta = "arrow"). As in the Principate, it is likely that many non-sagittarii regiments also contained some archers. Mounted archers appear to have been exclusively in light cavalry units.[17] Archer units, both foot and mounted, were present in the comitatus.[150] In the border forces, only mounted archers are listed in the Notitia, which may indicate that many limitanei infantry regiments contained their own archers.[151]

A distinctive feature of the late army is the appearance of independent units of artillery, which during the Principate appears to have been integral to the legions. Called ballistarii (from ballista = "catapult"), 7 such units are listed in the Notitia, all but one belonging to the comitatus. But a number are denoted pseudocomitatenses, implying that they originally belonged to the border forces. The purpose of independent artillery units was presumably to permit heavy concentration of firepower, especially useful for sieges. However, it is likely that many ordinary regiments continued to possess integral artillery, especially in the border forces.[152]

The Notitia lists a few units of presumably light infantry with names denoting specialist function: superventores and praeventores ("interceptors") exculcatores ("trackers"), exploratores ("scouts"). At the same time, Ammianus describes light-armed troops with various terms: velites, leves armaturae, exculcatores, expediti. It is unclear from the context whether any of these were independent units, specialist sub-units, or indeed just detachments of ordinary troops specially armed for a particular operation.[153] The Notitia evidence implies that, at least in some cases, Ammianus could be referring to independent units.

Foederati

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Outside the regular army were substantial numbers of allied forces, generally known as foederati (from foedus = "treaty") or symmachi in the East. The latter were forces supplied either by barbarian chiefs under their treaty of alliance with Rome or dediticii.[154] Such forces were employed by the Romans throughout imperial history e.g. the battle scenes from Trajan's Column in Rome show that foederati troops played an important part in the Dacian Wars (101–6).[155]

In the 4th century, as during the Principate, these forces were organised into ill-defined units based on a single ethnic group called numeri ("troops", although numerus was also the name of a regular infantry unit).[156] They served alongside the regular army for the duration of particular campaigns or for a specified period. Normally their service would be limited to the region where the tribe lived, but sometimes could be deployed elsewhere.[157] They were commanded by their own leaders. It is unclear whether they used their own weapons and armour or the standard equipment of the Roman army. In the late army, the more useful and long-serving numeri appear to have been absorbed into the regular late army, rapidly becoming indistinguishable from other units.[158]

Rekrutierung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Römer

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]During the Principate, it appears that most recruits, both legionary and auxiliary, were volunteers (voluntarii). Compulsory conscription (dilectus) was never wholly abandoned, but was generally only used in emergencies or before major campaigns when large numbers of additional troops were required.[159] In marked contrast, the late army relied mainly on compulsion for its recruitment of Roman citizens. Firstly, the sons of serving soldiers or veterans were required by law to enlist. Secondly, a regular annual levy was held based on the indictio (land tax assessment). Depending on the amount of land tax due on his estates, a landowner (or group of landowners) would be required to provide a commensurate number of recruits to the army. Naturally, landowners had a strong incentive to keep their best young men to work on their estates, sending the less fit or reliable for military service. There is also evidence that they tried to cheat the draft by offering the sons of soldiers (who were liable to serve anyway) and vagrants (vagi) to fulfil their quota.[44]

However, conscription was not in practice universal. Firstly, a land-based levy meant recruits were exclusively the sons of peasants, as opposed to townspeople.[44] Thus some 20% of the empire's population was excluded.[160] In addition, as during the Principate, slaves were not admissible. Nor were freedmen and persons in certain occupations such as bakers and innkeepers. In addition, provincial officials and curiales (city council members) could not enlist. These rules were relaxed only in emergencies, as during the military crisis of 405–6 (Radagaisus' invasion of Italy and the great barbarian invasion of Gaul).[161] Most importantly, the conscription requirement was often commuted into a cash levy, at a fixed rate per recruit due. This was done for certain provinces, in certain years, although the specific details are largely unknown. It appears from the very slim available evidence that conscription was not applied evenly across provinces but concentrated heavily in the army's traditional recruiting areas of Gaul (including the two Germaniae provinces along the Rhine) and the Danubian provinces, with other regions presumably often commuted. An analysis of the known origins of comitatenses in the period 350–476 shows that in the Western army, the Illyricum and Gaul dioceses together provided 52% of total recruits. Overall, the Danubian regions provided nearly half of the whole army's recruits, despite containing only three of the 12 dioceses.[162] This picture is much in line with the 2nd century position.[163]

Prospective recruits had to undergo an examination. Recruits had to be 20–25 years of age, a range that was extended to 19–35 in the later 4th century. Recruits had to be physically fit and meet the traditional minimum height requirement of 6 Roman feet (5 ft 10in, 175 cm) until 367, when it was reduced to 5 Roman feet and 3 Roman palms (5 ft 7in, 167 cm).[164]

Once a recruit was accepted, he was branded to facilitate recognition if he attempted to desert. The recruit was then issued with an identification disk (which was worn around the neck) and a certificate of enlistment (probatoria). He was then assigned to a unit. A law of 375 required those with superior fitness to be assigned to the comitatenses.[165] In the 4th century, the minimum length of service was 20 years (24 years in some limitanei units).[166] This compares with 25 years in both legions and auxilia during the Principate.

The widespread use of conscription, the compulsory recruitment of soldiers' sons, the relaxation of age and height requirements and the branding of recruits all add up to a picture of an army that had severe difficulties in finding, and retaining, sufficient recruits.[167] Recruitment difficulties are confirmed in the legal code evidence: there are measures to deal with cases of self-mutilation to avoid military service (such as cutting off a thumb), including an extreme decree of 386 requiring such persons to be burnt alive.[166] Desertion was clearly a serious problem, and was probably much worse than in the Principate army, since the latter was mainly a volunteer army. This is supported by the fact that the granting of leave of absence (commeatus) was more strictly regulated. While in the 2nd century, a soldier's leave was granted at the discretion of his regimental commander, in the 4th century, leave could only be granted by a far senior officer (dux, comes or magister militum).[168][169] In addition, it appears that comitatus units were typically one-third understrength.[170] The massive disparity between official and actual strength is powerful evidence of recruitment problems. Against this, Elton argues that the late army did not have serious recruitment problems, on the basis of the large numbers of exemptions from conscription that were granted.[171]

Barbaren

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Barbari ("barbarians") was the generic term used by the Romans to denote peoples resident beyond the borders of the empire, and best translates as "foreigners" (it is derived from a Greek word meaning "to babble": a reference to their outlandish tongues).

Most scholars believe that significant numbers of barbari were recruited throughout the Principate by the auxilia (the legions were closed to non-citizens).[166][172] However, there is little evidence of this before the 3rd century. The scant evidence suggests that the vast majority, if not all, of auxilia were Roman peregrini (second-class citizens) or Roman citizens.[173] In any case, the 4th-century army was probably much more dependent on barbarian recruitment than its 1st/2nd-century predecessor. The evidence for this may be summarised as follows:

- The Notitia lists a number of barbarian military settlements in the empire. Known as laeti or gentiles ("natives"), these were an important source of recruits for the army. Groups of Germanic or Sarmatian tribespeople were granted land to settle in the Empire, in return for military service. Most likely each community was under a treaty obligation to supply a specified number of troops to the army each year.[166] The resettlement within the empire of barbarian tribespeople in return for military service was not a new phenomenon in the 4th century: it stretches back to the days of Augustus.[174] But it does appear that the establishment of military settlements was more systematic and on a much larger scale in the 4th century.[175]

- The Notitia lists a large number of units with barbarian names. This was probably the result of the transformation of irregular allied units serving under their own native officers (known as socii, or foederati) into regular formations. During the Principate, regular units with barbarian names are not attested until the 3rd century and even then rarely e.g. the ala I Sarmatarum attested in 3rd-century Britain, doubtless an offshoot of the Sarmatian horsemen posted there in 175.[176]

- The emergence of significant numbers of senior officers with barbarian names in the regular army, and eventually in the high command itself. In the early 5th century, the Western Roman forces were often controlled by barbarian-born generals, such as Arbogast, Stilicho and Ricimer.[177]

- The adoption by the 4th century army of barbarian (especially Germanic) dress, customs and culture, suggesting enhanced barbarian influence. For example, Roman army units adopted mock barbarian names e.g. Cornuti = "horned ones", a reference to the German custom of attaching horns to their helmets, and the barritus, a German warcry. Long hair became fashionable, especially in the palatini regiments, where barbarian-born recruits were numerous.[178]

Quantification of the proportion of barbarian-born troops in the 4th century army is highly speculative. Elton has the most detailed analysis of the meagre evidence. According to this, about a quarter of the sample of army officers was barbarian-born in the period 350–400. Analysis by decade shows that this proportion did not increase over the period, or indeed in the early 5th century. The latter trend implies that the proportion of barbarians in the lower ranks was not much greater, otherwise the proportion of barbarian officers would have increased over time to reflect that.[179]

If the proportion of barbarians was in the region of 25%, then it is probably much higher than in the 2nd-century regular army. If the same proportion had been recruited into the auxilia of the 2nd-century army, then in excess of 40% of recruits would have been barbarian-born, since the auxilia constituted 60% of the regular land army.[8] There is no evidence that recruitment of barbarians was on such a large scale in the 2nd century.[33] An analysis of named soldiers of non-Roman origin shows that 75% were Germanic: Franks, Alamanni, Saxons, Goths, and Vandals are attested in the Notitia unit names.[180] Other significant sources of recruits were the Sarmatians from the Danubian lands; and Armenians and Iberians from the Caucasus region.[181]

In contrast to Roman recruits, the vast majority of barbarian recruits were probably volunteers, drawn by conditions of service and career prospects that to them probably appeared desirable, in contrast to their living conditions at home. A minority of barbarian recruits were enlisted by compulsion, namely dediticii (barbarians who surrendered to the Roman authorities, often to escape strife with neighbouring tribes) and tribes who were defeated by the Romans, and obliged, as a condition of peace, to undertake to provide a specified number of recruits annually. Barbarians could be recruited directly, as individuals enrolled into regular regiments, or indirectly, as members of irregular foederati units transformed into regular regiments.[182]

Ränge, Sold und Belohnung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Normale Soldaten

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]At the base of the rank pyramid were the common soldiers: pedes (infantryman) and eques (cavalryman). Unlike his 2nd century counterpart, the 4th-century soldier's food and equipment was not deducted from his salary (stipendium), but was provided free.[183] This is because the stipendium, paid in debased silver denarii, was under Diocletian worth far less than in the 2nd century. It lost its residual value under Constantine and ceased to be paid regularly in mid 4th century.[184]

The soldier's sole substantial disposable income came from the donativa, or cash bonuses handed out periodically by the emperors, as these were paid in gold solidi (which were never debased), or in pure silver. There was a regular donative of 5 solidi every five years of an Augustus reign (i.e. one solidus p.a.) Also, on the accession of a new Augustus, 5 solidi plus a pound of silver (worth 4 solidi, totaling 9 solidi) were paid. The 12 Augusti that ruled the West between 284 and 395 averaged about nine years per reign. Thus the accession donatives would have averaged about 1 solidus p.a. The late soldier's disposable income would thus have averaged at least 2 solidi per annum. It is also possible, but undocumented, that the accession bonus was paid for each Augustus and/or a bonus for each Caesar.[185] The documented income of 2 solidi was only a quarter of the disposable income of a 2nd-century legionary (which was the equivalent of ca. 8 solidi).[186] The late soldier's discharge package (which included a small plot of land) was also minuscule compared with a 2nd-century legionary's, worth just a tenth of the latter's.[187][188]

Despite the disparity with the Principate, Jones and Elton argue that 4th century remuneration was attractive compared to the hard reality of existence at subsistence level that most recruits' peasant families had to endure.[189] Against that has to be set the clear unpopularity of military service.

However, pay would have been much more attractive in higher-grade units. The top of the pay pyramid were the scholae elite cavalry regiments. Next came palatini units, then comitatenses, and finally limitanei. There is little evidence about the pay differentials between grades. But that they were substantial is shown by the example that an actuarius (quartermaster) of a comitatus regiment was paid 50% more than his counterpart in a pseudocomitatensis regiment.[190]

Regimentsoffiziere

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Regimental officer grades in old-style units (legiones, alae and cohortes) remained the same as under the Principate up to and including centurion and decurion. In the new-style units, (vexillationes, auxilia, etc.), ranks with quite different names are attested, seemingly modelled on the titles of local authority bureaucrats.[191] So little is known about these ranks that it is impossible to equate them with the traditional ranks with any certainty. Vegetius states that the ducenarius commanded, as the name implies, 200 men. If so, the centenarius may have been the equivalent of a centurion in the old-style units.[192] Probably the most accurate comparison is by known pay levels:

| Multiple of basic pay (2nd c.) or annona (4th c.) |

2nd c. cohors (ascending ranks) |

2nd c. ala (ascending ranks) |

XXX | 4th c. units (ascending ranks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pedes (infantryman) | gregalis (cavalryman) | pedes (eques) | |

| 1.5 | tesserarius ("corporal") | sesquiplicarius ("corporal") | semissalis | |

| 2 | signifer (centuria standard-bearer) optio (centurion's deputy) vexillarius (cohort standard-bearer) |

signifer (turma standard-bearer) curator? (decurion's deputy) vexillarius (ala standard-bearer) |

circitor biarchus | |

| 2.5 to 5 | centenarius (2.5) ducenarius (3.5) senator (4) primicerius (5) | |||

| Over 5 | centurio (centurion) centurio princeps (chief centurion) beneficiarius? (deputy cohort commander) |

decurio (turma commander) decurio princeps (chief decurion) beneficiarius? (deputy ala commander) |

NOTE: Ranks correspond only in pay scale, not necessarily in function

The table shows that the pay differentials enyjoyed by the senior officers of a 4th-century regiment were much smaller than those of their 2nd-century counterparts, a position in line with the smaller remuneration enjoyed by 4th-century high administrative officials.

Regiments- und Corpsoffiziere

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]| Pay scale (multiple of pedes) |

Rank (ascending order) |

No. of posts (Notitia) |

Job description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Protector | Several hundreds (200 in domestici under Julian) |

cadet regimental commander |

| n.a. | Tribunus (or praefectus) | ca. 800 | regimental commander |

| n.a. | Tribunus comes | n.a. | (i) commander, protectores domestici (comes domesticorum) (ii) commander, brigade of two twinned regiments or (iii) some (later all) tribuni of scholae (iv) some staff officers (tribuni vacantes) to magister or emperor |

| 100 | Dux (or, rarely, comes) limitis | 27 | border army commander |

| n.a. | Comes rei militaris | 7 | (i) commander, smaller regional comitatus |

| n.a. | Magister militum (magister equitum in West) |

4 | commander, larger regional comitatus |

| n.a. | Magister militum praesentalis (magister utriusque militiae in West) |

3 | commander, imperial escort army |

The table above indicates the ranks of officers who held a commission (sacra epistula, lit: "solemn letter"). This was presented to the recipient by the emperor in person at a dedicated ceremony.[195]

Cadet regimental commanders (protectores)

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]A significant innovation of the 4th century was the corps of protectores, which contained cadet senior officers. Although protectores were supposed to be soldiers who had risen through the ranks by meritorious service, it became a widespread practice to admit to the corps young men from outside the army (often the sons of senior officers). The protectores formed a corps that was both an officer training-school and pool of staff officers available to carry out special tasks for the magistri militum or the emperor. Those attached to the emperor were known as protectores domestici and organised in four scholae under a comes domesticorum. After a few years' service in the corps, a protector would normally be granted a commission by the emperor and placed in command of a military regiment.[197]

Regimental commanders (tribuni)