Benutzer:Shi Annan/Jean Bolikango

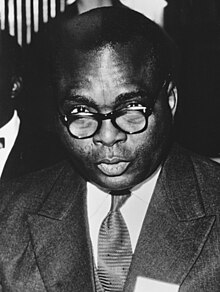

Jean Bolikango (Bolikango Akpolokaka Gbukulu Nzete Nzube, geb. 4. Februar 1909 gest. 17. Februar 1982) war ein Pädagoge, Schriftsteller und Politiker im Kongo. Er war zwei Mal Deputy Prime Minister der Republic of the Congo (République du Congo, Léopoldville): im September 1960 und von Februar bis August 1962. Er njoying substantial popularity among the Bangala people, he headed the Parti de l'Unité Nationale and worked as a key opposition member in Parliament in the early 1960s.

Bolikango began his career in the Belgisch-Kongo as a teacher in Catholic schools, and became a prominent member of Congolese society as the leader of a cultural association. He wrote an award-winning novel and worked as a journalist before turning to politics in the late 1950s. Though he held a top communications post in the colonial administration, he became a leader in the push for independence, making him one of the "fathers of independence" in the Congo. The Republic of the Congo became independent in 1960 and Bolikango attempted to organise a national political base that would support his bid for a prestigious office in the new government. He succeeded in establishing the Parti de l'Unité Nationale and promoted both a united Congo and strong ties with Belgium. Older than most of his contemporaries and commanding significant respect—especially among his Bangala peers, he was seen as the Congo's "elder statesman". Regardless, his attempts to secure a position in the government failed and he became a leading member of the opposition in Parliament.

As the country became embroiled in a domestic crisis, the first government was dislodged and succeeded by several different administrations. Bolikango served as Deputy Prime Minister in one of the new governments before a partial state of stability was reestablished in 1961. He mediated between warring factions in the Congo and briefly served once again as Deputy Prime Minister in 1962 before returning to the parliamentary opposition. After Joseph-Désiré Mobutu took power in 1965, Bolikango became a minister in his government. Mobutu soon dismissed him but appointed him to the political bureau of the Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution. Bolikango left the bureau in 1970. He left Parliament in 1975 and died seven years later. His grandson created the Jean Bolikango Foundation in his memory to promote social progress. The President of the Congo posthumously awarded Bolikango a medal in 2005 for his long career in public service.

Early life

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Jean Bolikango was born in Léopoldville, Belgian Congo, on 4 February 1909[1]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} to a Bangala family from Équateur Province.[2]LaFontaine|2008|p=218[3]Bolikango was categorised broadly as a Ngala by the residents of Léopoldville, though his heritage traced more specifically to the Ngombe people of the Lisala region.[4]Bennett|1972|p=301}}}} In 1917 he enrolled in St. Joseph's Institute, graduating in December 1925 after six years of primary school, two years of pedagogical studies, and one year of stenography and typing courses.[5]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} He became a licensed primary school teacher the following year.[6]LaFontaine|2008|p=218}} Bolikango taught at Scheutist schools[7]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} and finally St. Joseph's Institute until 1958. He instructed a total of 1,300 students,[8] including future Prime Minister Joseph Iléo, future Prime Minister Cyrille Adoula, future Minister of Finance Arthur Pinzi, future Minister of Social Affairs Jacques Massa,[9]LaFontaine|2008|p=219}} future dramatist Albert Mongita, and future Catholic Cardinal Joseph Malula.[10]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} In 1946 he became the president of the Association des Anciens élèves des pères de Scheut[11]Association of Former Students of the Fathers of Scheut; an alumni association for Congolese who were educated by Scheut Missionaries}} (ADAPÉS), a position he held until his death.[8]

That year Bolikango, as the leader of the capital évolués, worked closely with missionary Raphaël de la Kethulle de Ryhove to establish the Union des Interets Sociaux Congolais (UNISCO), a cultural society for leaders of elite Congolese associations.[12]LaFontaine|2008|p=218}} He then became its vice president.[13]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} The organisation was viewed favorably by the colonial administration for its attachment to Belgian social ideals, though it would later become a forum for revolutionary politics.[14]LaFontaine|2008|p=155}}[15]Kasongo|1998|p=85}} In 1954 Bolikango founded and, for a time, served as general chairman of the Liboka Lya Bangala, the first Bangala ethnic association, based in Léopoldville.[16]LaFontaine|2008|p=218}}[17]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}}[18]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} By 1957 it encompassed 48 affiliated tribal organisations and had 50,000 members.[19]Young|2015|p=245}} He authored a novel in Lingala entitled Mondjeni-Mobé: Le Hardi, which won a consolation prize for creative writing from the Conference on African Studies at the International Fair in Ghent in 1948.[20]FASD|1962|p=200}}[21]Botombele|1976|p=27}}[22]African Book Awards Database|2008}}[23]According to Mulumba and Makombo, Bolikango received the second place prize.[24]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} Jadot wrote that Bolikango received the second of two consolation prizes, worth 1,000 francs. Jadot|1959|p=39}}}} He also made a submission to the 1949 contest, but no prize was awarded.[25]Jadot|1959|p=39}} Bolikango soon befriended Joseph Kasa-Vubu and sponsored his election as secretary-general of ADAPÉS in order to bring him into UNISCO, thereby furthering the latter's political standing.[26]LaFontaine|2008|p=217}} Bolikango eventually married a woman named Claire.[27]Kanza|1994|p=130}} He also obtained a carte de mérite civique[28]The carte de mérite civique (civic merit card) could be granted to any Congolese who had no criminal record, did not practice polygamy, abandoned traditional religion, and had some degree of education. Cardholders were given an improved legal status and were exempt from certain restrictions on travel into European districts.[29]Geenen|2019|p=114}}}} from the Belgian administration and served on the commission responsible for its assignment to deserving Congolese.[30]Omasombo Tshonda|Verhaegen|2005|p=386}}

Bolikango first went abroad when he attended Kethulle de Ryhove's funeral in Belgium in 1956. During his return trip he stopped in Paris to meet African members of the French Parliament.[31]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} That year he met a handful of his former students and other Congolese leaders in his home. Together they drafted the first Congolese political manifesto, Manifeste de Conscience Africaine.[32] In 1958 he resigned from his teaching post and went to Brussels to represent Catholic education at the Expo 58 event, holding responsibility for public relations at the Missions Pavilion. This led him to study press, radio, television, film, and mass education techniques at the Office of Information and Public Relations for the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi. In August 1959 he was appointed Assistant Commissioner of Information in the office,[33]Merriam|1961|p=164}} making him one of only two Congolese to ever hold a second grade civil servant position in the Belgian colonial administration.[34]Hoskyns|1965|p=12}}[35]The colonial administration had eight grades of service. No Congolese served in the first grade. Hoskyns|1965|p=12}}}} In that capacity he initiated a comparative study of information services across Sub-Saharan Africa, compiled details on Congolese politicians, gave numerous speeches, and helped design Bantu language courses at the University of Ghent.[36]Merriam|1961|pp=164–165}} He regularly wrote for the Léopoldville monthly La Voix du Congolais[37] and the Catholic newspaper La Croix du Congo. In 1960 Bolikango started his own newspaper, La Nation Congalaise.[38]LaFontaine|2008|p=218}} In his contributions he frequently advocated for equal pay between black and whites for the same labor.[37]

Political career

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Beliefs

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Bolikango was older than most of his political contemporaries[32] and was regarded as the Congo's "elder statesman".[39]Africa Report|1960|p=4}} He was labeled conservative and "pro-Belgian".[40]Yearbook|1963|p=178}} He considered the Senegalese poet and politician Léopold Sédar Senghor to be a principal influence on his beliefs. He also admired Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Côte d'Ivoire for his "wisdom and calmness".[41]Legum|1961|p=102}} Like other members of the original Congolese establishment, Bolikango sought a gradual decolonisation process during which the Belgian authorities were to be amicably negotiated with.[42]Nzongola-Ntalaja|2014|p=62}} He believed the Congo should be united in a broad fashionVorlage:Efn Conversely, Segal writes that Bolikango was "willing to concede a measure of provincial autonomy" but was "opposed to federation".[43]Segal|1971|p=87}} Nzongola-Ntalaja states that Bolikango was "[i]nitially a unitarist" and "opted for federalism as soon as he failed to gain an important post in Kinshasa, having lost the presidential election to Kasavubu". Nzongola-Ntalaja|1982|p=119}}}} and supported the formation of a union of African states.[44]Merriam|1961|p=165}}

Early organisation

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

In 1953 Bolikango became a substitute member of the Conseil de la province de Léopoldville.[45]Council of Léopoldville Province}} He served in the post for three years.[46]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=65}} In December 1957 he unsuccessfully entered Léopoldville's first municipal elections.[47]Young|2015|p=120}} The Bangala as a whole did not do well in the campaign; their only form of organisation was Bolikango's Liboka Lya Bangala, an association with little cohesion.[48]Merriam|1961|p=158}} Following the electoral defeats, Bolikango decided to organise the Interfédérale,[49]Interfederal}} a federation among various regional and ethnic groups of the northern Congo that became the basis of his new Parti de l'unité Congolaise.[50]Party of Congolese Unity}} Almost immediately after its creation the party collapsed due to ethnic differences.[51]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}} In April 1959 Patrice Lumumba asked Bolikango to become director of his nationalist political party, the Mouvement National CongolaisVorlage:Efn (MNC), but he never committed to a decision.[52]Merriam|1961|pp=143–144}} In the autumn of 1959 the Interfédérale became a part of the Parti National du Progrès[53]Party of National Progress}} (PNP).[54]FASD|1962|p=344}} Bolikango did not follow them, instead founding the Front de l'unite Bangala[55]Front of United Bangala}} (FUB), a political party representing the Bangala people of the northeastern Congo.[56]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}} Among them he was a popular figure; Bangala nicknames for him included "the Sage" and even "Moses".[57]Legum|1961|p=101}} He hoped that by promoting the idea of a grande ethnie bangalaVorlage:Efn he could enhance his political prospects.[58]Young|2015|p=245}} The Bangala were only unified as a political faction in the capital, so he began to look elsewhere for support.[59]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}} He was also a cofounder of the short-lived Mouvement pour le Progres National Congolais,[60]Movement for Congolese National Progress}} a party formed by attendees of the Brussels exposition.[61]Lemarchand|1964|p=281[62]Gérard-Libois|1960|p=290}}

Bolikango soon thereafter created the Association des ressortisants du Haut-Congo[63]Association of Upper Congo Peoples}} (ASSORECO).[64]Brassinne|1989|loc= paragraph 30}} From 20 January to 20 February 1960 Bolikango attended the Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference in Brussels to discuss the Congo's future under Belgian rule, serving as the leading delegate for ASSORECO.[65]C. Van Cortenbergh|1960|p=62}} He was assisted by his political adviser Victor Promontorio, whom he knew since their childhood.[66]Promontorio|1965|loc=back cover}} Bolikango was made a member of the conference's bureau.[67]Kanza|1994|p=81}} During the discussions he made an unexpectedly sharp denunciation of Belgian propaganda.[68]Legum|1961|pp=101–102}} He also acted as the spokesperson for the Front Commun, (Common Front) the political umbrella for all the Congolese delegations.[69]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} In that capacity on 27 January he publicly revealed that independence would be granted to the Congolese on 30 June.[70]Radio Okapi|2016}} Following the conference he traveled with a colleague to Bonn, Federal Republic of Germany to meet local politicians.[71]Forum der freien Welt|1960|p=33}}

Attempts at consolidation

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]To consolidate his political power in Équateur Province, Bolikango summoned a congress to Lisala that lasted from 24 March to 3 April. Like his own party, the other political groups of Équateur lacked the necessary support to make significant gains in the upcoming independent elections. Bolikango was eager to win a prominent government office and aimed to form a broad coalition with the Ngombe, Mongo, and Ngwaka peoples and other minorities in the province to achieve it. This could be best accomplished, in his view, through an alliance of his own groups, the FUB and ASSORECO, with UNIMO, FEDUNEC, UNILAC, and local chiefs who had not already put their support behind the PNP.[72]Lemarchand|1964|p=280}}

"Bolikango was one of those Congolese politicians who believed that honesty and keeping one's word were the most important characteristics of political men. He could not conceive of anyone's using deceit, still less violence or brutality, as a tactic for success."|source= Thomas Kanza's opinion on Bolikango's approach towards politics during his bid for the presidency Kanza|1994|p=124

In his opening address at the congress, Bolikango said that while "parties based on ethnic foundations" made the first step toward a unified Congo, the "national interest" of the country rested upon a "unity of will". He enumerated that this "does not mean that each ethnic group must abandon its own characteristics, but that through these differences one must endeavour to form a harmonious ensemble."[73]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}} The UNIMO leadership was skeptical of Bolikango's unified outlook for the Congo and remained independent, although he secured the support of the Ngombe, some of the Ngwaka and Bangala, and chiefs from the Lisala, Bongandanga, and Bumba regions.[74]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}} The FUB made an alliance with ASSORECO and FEDUNEC, transforming into the Parti de l'Unité Nationale (Party of National Unity PUNA).[75]Lemarchand|1964|p=280}} In spite of its attempts to garner more national appeal, the new party retained its regional bias and failed to amass substantial outside support, costing Bolikango much of his backing in Léopoldville.[76]LaFontaine|2008|p=218[77]Lemarchand|1964|p=281}} Still, this reformed political base allowed him to win a position as a national deputy from the Mongala district in the May 1960 national election by 15,000 votes.[8] He used his position as the president of PUNA to mediate a dispute between the party and minority alliances in Équateur and create a coalition provincial government.[78]CRISP no. 70|1960|loc=paragraph 45}} After the elections PUNA gradually pulled apart into two different wings, one led by Bolikango and the other by Équateur Provincial President Laurent Eketebi.[79]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|p=190}}

Meanwhile, the MNC sharply criticised Bolikango's connections with the Belgians, undermining his reputation in both Équateur and the capital.[80]LaFontaine|2008|p=219}} The Alliance des Bakongo (Bakongo Alliance ABAKO) also despised him due to his support for Catholic missions and the perception that he was "pro-white".[81]Omasombo Tshonda|Verhaegen|2005|p=386}} He spent the month of May touring the Congo, claiming that he had the support of other party leaders in an alliance against Lumumba and the MNC. This opposition alliance was soon announced as the Cartel d'Union Nationale.[82]CRISP no. 70|1960|loc=paragraphs 28, 55–57}} As Lumumba was assembling his proposed cabinet, the Chamber of Deputies convened on 21 June to elect its officers. Bolikango made a bid to be President of the Chamber, but lost the vote to the MNC candidate, Joseph Kasongo, 74 to 58.[83]FASD|1962|p=344[84]CRISP no. 70|1960|loc=paragraphs 89–90}} According to Kent, the result was facilitated by the bribing of 13 deputies by Jacques Lumbala, an ally of Lumumba, who would have otherwise been partial to Bolikango. Kent|2010|loc=2: The elimination of Lumumba and the establishment of the Adoula government, September 1960–August 1961}}}} The subsequent election of the Senate's officers also indicated an MNC advantage. Realising that Lumumba's bloc controlled Parliament, several members of the Cartel became eager to negotiate for a coalition government so they could share power, especially Bolikango,[85]CRISP no. 70|1960|loc=paragraph 104}} who hoped to secure the position of Defence Minister. This did not occur,[32] but he did exact a written pledge from Lumumba of support for his bid to become the first President of the Republic of the Congo in exchange for his party's backing of Lumumba's government.[86]CRISP no. 70|1960|loc=paragraph 105}}

Bolikango faced his former protégé, Joseph Kasa-Vubu of ABAKO, in the parliamentary vote for the presidency. Lumumba realised that the Belgians would only accept him as Prime Minister if Kasa-Vubu held office, so he switched allegiances, privately dismissing Bolikango as a "pawn of Belgium and a protégé of the Catholics", and secretly endorsing Kasa-Vubu. Bolikango lost the parliamentary vote 159 to 43[87]Frindethie|2016|p=220}} and was left infuriated.[88]Kanza|1994|p=123}} In addition to Lumumba's duplicity, Bolikango also suffered in the election due to his recent association with the colonial administration and his breaking with the Cartel to negotiate with Lumumba.[89]CRISP no. 70|1960|loc=paragraph 128}} According to his friend, Thomas Kanza, the loss was "the most bitter failure in his entire career."[90]Kanza|1994|p=130}} He then helped organise an anti-MNC coalition in Parliament.[91]Hoskyns|1965|p=73}}

Congo Crisis

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]"Where are the freedom and security for all, promised with independence?...[H]ow is it that under Belgian rule we were less ill-treated than we are today? Similarly, how is it conceivable that the country's economy, so prosperous that those who yesterday, under the colonial regime, were sure of their bread, are no longer sure of it for tomorrow? Today, instead of bread, we are offered curfew and bayonets; we once knew the animation of the city, the freedom to live. Now the streets are deserted, occupied militarily. Is that independence or dependence?"|source=Statement by Bolikango on the Congo Crisis to the press, 2 August 1960 CRISP no. 78|1960|loc=paragraph 72}}}}

During the Congo Crisis that followed Congolese independence, Bolikango acted as a United States Central Intelligence Agency informant.[92]Howard|2013|p=301}} Early in the crisis he accused Prime Minister Lumumba of ignoring opposition groups and deliberately stifling dissent;[93]Bacquelaine|Willems|Coenen|2001|p=76}} on 3 August he officially denounced Lumumba's policies. Five days later he announced that he would support the formation of a separate republic in Équateur Province.[94]CRISP no. 78|1960|loc=paragraph 28}} In return, Lumumba accused him of plotting the secession of the region.[95]Daily Sun|1960|p=2}} On 1 September Bolikango was arrested in Gemena on Lumumba's orders, ostensibly for committing secessionist activities and planning assassinations of both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu, and brought to the capital. Lumumba told Parliament that Bolikango had been arrested by the Équateur provincial government.[96]Kanza|1994|p=294}}}} This led to demonstrations by his supporters throughout the city on the following day.[97]Bacquelaine|Willems|Coenen|2001|p=77}} On 5 September the Chamber of Deputies, particularly upset by Bolikango's arrest, passed a resolution demanding that all detained members of Parliament be released.[98]Kanza|1994|pp=285–286}} Soon thereafter, President Kasa-Vubu dismissed Lumumba from office and replaced him with Joseph Iléo.[99]Young|2015|p=326}} Sympathetic soldiers freed Bolikango from his confinement on 6 September.[100]Merriam|1961|p=165}} During Iléo's brief first term from 13 to 20 September Bolikango served as Minister of Information and Minister of Defence.[101]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} In December he attended a Francophone-African conference in Brazzaville as part of a Congolese government delegation.[102]De Witte|2002|p=69}}

During Iléo's second term from 9 February until 1 August 1961 Bolikango held the post of Deputy Prime Minister.[103]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} By then he felt threatened by the sudden collapse of political unity in the Congo and supported the government's efforts at re-centralisation.[104]Willame|1972|pp=37, 39}} He participated in the Tananarive and Coquilhatville conferences of March and April 1961, representing Équateur and Ubangi, respectively, to seek a compromise on constitutional issues.[105]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} Throughout June he worked alongside Cyrille Adoula and Marcel Lihau to negotiate a settlement between the central government and a rival Free Republic of the Congo in the eastern portion of the country.[106]Higgins|1980|p=421}} This culminated in a conference in July that resulted in the election of Adoula as Prime Minister. Bolikango was certain that he would also be elected as President but Kasa-Vubu retained the office.[107]O'Brien|1962|p=189 It was widely rumoured in the Congo that Bolikango was offered the position of Third Deputy Prime Minister but turned it down in anticipation of an opportunity to challenge Kasa-Vubu. Hoskyns|1965|p=378}}}}

After the conference Bolikango helped to mediate negotiations between Adoula and secessionist figure Moïse Tshombe, leader of the breakaway State of Katanga.[8] Bolikango claimed that he alone could resolve the situation by sitting "Bantu fashion with legs out stretched" around a table with Tshombe.[32] He scheduled a political conference to take place in Stanleyville to create a new political party with Antoine Gizenga with the intent of isolating Kasa-Vubu and ABAKO in Parliament so he could remove the former from the presidency and replace him. The plans dissolved after Gizenga was arrested in January 1962.[108]Africa|1962|p=8}} On 13 February Bolikango was appointed Deputy Prime Minister.Vorlage:Sfn On 12 July Adoula downsized his government and dismissed him from his post.[109]Yearbook|1963|p=178}} He then re-entered the parliamentary opposition and, by August, was working with Rémy Mwamba and Christophe Gbenye (both ex-ministers also dismissed from Adoula's government) to try and secure support to dislodge Adoula. Bolikango was the opposition's favorite to replace the Prime Minister.[110]CIA|1962|pp=14–15}} In 1963 following the defeat of Katanga, he managed to organise an opposition coalition to Adoula's government, consisting of ABAKO, leftist followers of Lumumba (by then killed) and Gizenga, and Tshombe's Confédération des associations tribales du Katanga (Confederation of Tribal Associations of Katanga, CONAKAT).[32] He also foiled an attempt by one of Adoula's ministers to establish a pro-government party in Équateur.[111] That year Parliament was adjourned and Bolikango's term as a national deputy ended.[112]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|p=223}} In late 1963 Laurent Eketebi left PUNA and allied himself with the Budja tribal minority in the provincial assembly, destroying the concept of a unified Bangala tribe that Bolikango had used to elevate his social and political standing.[113]Willame|1972|pp=53, 56}}

In 1962 Parliament assented to the partitioning of the Congo's six provinces into smaller political units. The subdivision damaged PUNA's political clout, as it had a strong following in Coquilhatville, the Équateur capital, but not in the outlying areas, where it relied on control of the provincial administration to ensure its presence. Bolikango had opposed the splitting of Équateur, and in 1965 he made provincial reunification a key part of his parliamentary campaign platform.[114]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|p=207}} In the 1965 elections he was reelected to a second term in the Chamber of Deputies on a PUNA–Convention Nationale Congolaise (Congolese National Convention, CONACO) ticket.[115]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66[116]Marchés tropicaux et méditerranéens|1966}} He received 53,083 preferential votes, making him the most popular Congolese representative of his respective constituency, second only to Tshombe in southern Katanga.[117]Willame|1972|p=53}} Nevertheless, his provincial reunification proposal met strong resistance from the deputies of Ubangi Province—one of the successor divisions to Équateur—and was not carried out.[118]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|p=207}}

Mobutu regime

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Joseph-Désiré Mobutu seized power in November 1965, and on 24 November Bolikango was appointed Minister of Public Works.[119]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66[120]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|p=220}} Mobutu also intervened in a territorial dispute in the former Équateur Province and awarded contested land to Ubangi over Moyen-Congo—the new province Bolikango represented. Upset over the outcome, Bolikango convened a meeting of parliamentarians from both provinces in February 1966 to discuss the restoration of Équateur. His ideas attracted more support than during his previous attempt, as there were provincial assemblymen in Ubangi already petitioning their government for reunification and numerous CONACO politicians had initiated a campaign to eliminate Cuvette-Centrale Province after losing a local struggle for power. With Mobutu's support, Équateur was restored on 11 April.[121]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|pp=207–208}}

On 4 April Mobutu dismissed Bolikango from his ministerial post, ostensibly for "lack of discipline and refusing to follow received orders."[122]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66[123]Associated Press|1966}} This firing was the first of many Mobutu would use to pressure established Congolese politicians, though Bolikango was not left disadvantaged for long;[124]Young|Turner|2013|p=56}} on 4 July 1968 he was appointed to the political bureau of the Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution (Popular Movement of the Revolution, MPR), the state party, serving there until 16 December 1970.[125]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} Bolikango's second term as a national deputy ended in 1967.[126]Omasombo Tshonda|2015|p=223}} From 1970 until 1975 he served a final term in Parliament, representing the Kinshasa constituency.[127]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}}

In his later life Bolikango served as managing director of the Sogenco construction company and general delegate to the Société zaïroise de Matériaux and STK parastatals.[128]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} During the same time he made frequent trips to Lisala, where he remained a popular figure. Rumors surfaced in the capital that Bolikango was planning to use his regional political esteem for subversive purposes, so the Mobutu regime closely monitored his activities.[129]Schatzberg|1991|p=32}} Bolikango joined the MPR's central committee in September 1980. He died from an illness on 17 February 1982 in Liège, Belgium.[130]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|pp=65–66 According to Monga Monduka, Bolikango died on 22 February.[8]}}

Legacy

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Sociologist Ludo De Witte wrote of Bolikango as a "neo-colonial" politician who was "short-sighted and power-crazy".[131]De Witte|2002|p=63}} Bolikango is remembered in the Congo as one of the "fathers of independence".[132][133] The Fondation Jean Bolikango (Jean Bolikango Foundation) was created by Bolikango's grandson in his memory. The foundation focuses on supporting education and social progress.[8] In 2005 President Joseph Kabila posthumously awarded Bolikango a medal for dedication to civil service.[134] Bolikango was also a Commander of the National Order of the Leopard, member of the Royal Order of the Lion, and a recipient of the Benemerenti medal (1950), Medaille Commémorative du Voyage royal (Commemorative Medal of the Royal Voyage, 1955), gold medal of the Association Royale Sportive Congolaise (Royal Congolese Sport Association) and bronze and silver medals for other acts of public service.[135]Mulumba|Makombo|1986|p=66}} On 22 February 2007 a ceremony was held in Équateur to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his death.[8]

References

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- 30 juin 2016: la RDC célèbre son 56e anniversaire d'indépendance sur fond d'impasse politique. Radio Okapi, 30. Juni 2016, abgerufen am 20. Februar 2017 (französisch).

- Parti Unité Nationale Africaine (PUNA). In: Africa Report. 5. Jahrgang, Nr. 6. African-American Institute, 1960, ISSN 0001-9836, S. 4 (archive.org).

- African Book Awards Database. Indiana University Bloomington, 2008, archiviert vom am 12. September 2015; abgerufen am 21. August 2017.

- Area handbook for the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville). Band 1. American University Foreign Areas Studies Division, Washington D.C. 1962, OCLC 1347356 (google.com).

- Cabinet Member Fired by Mobutu, 16 April 1966, S. 2

- Vorlage:Citation

- The Belgo-Congolese Round Table: The historic days of February 1960. C. Van Cortenbergh, Brussels 1960, OCLC 20742268 (archive.org).

- Norman R. Bennett (Hrsg.): The International Journal of African Historical Studies. Band 5. Africana Publishing Company, Boston 1972 (google.com).

- Bokonga Ekanga Botombele: Cultural Policy in the Republic of Zaire. The Unesco Press, Paris 1976, ISBN 92-3101317-3 (unesco.org [PDF]).

- Jacques Brassinne: Les conseillers à la Table ronde belgo-congolaise. In: Courrier Hebdomadaire du CRISP. 38. Jahrgang, Nr. 1263–1264. Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques, Brussels 1989, S. 1–62, doi:10.3917/cris.1263.0001 (französisch, cairn.info).

- The case of a reluctant dragon. In: Africa. 3. Jahrgang, 1962, ISSN 0044-6475, S. 7–8 (google.com).

- Congo In: Corsicana Daily Sun, 2 September 1960

- Congo. In: Current Intelligence Weekly Summary. United States Central Intelligence Agency, 3. August 1962 (cia.gov ( des vom 23 January 2017 im Internet Archive)).

- Congo (Léo) In: Marchés tropicaux et méditerranéens, 1966, S. 1153 (french).

- Vorlage:Cite encyclopedia

- Le développement des oppositions au Congo. In: Courrier Hebdomadaire du CRISP. 78. Jahrgang, Nr. 32. Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques, 1960, S. 1–20, doi:10.3917/cris.078.0001 (französisch, cairn.info).

- J.S. LaFontaine: City Politics: A Study of Léopoldville 1962–63 (= American Studies). reprint Auflage. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, OCLC 237883398 (google.com).

- La formation du premier gouvernement congolais. In: Courrier Hebdomadaire du CRISP. n° 70. Jahrgang, Nr. 70. Centre de recherche et d'information socio-politiques, Brussels 1960, S. 1, doi:10.3917/cris.070.0001 (französisch, cairn.info).

- Forum der freien Welt. Band 2. Verlag Freie Welt, Illertissen 1960, OCLC 49600208 (google.com).

- K. Martial Frindethie: From Lumumba to Gbagbo: Africa in the Eddy of the Euro-American Quest for Exceptionalism. McFarland, Jefferson, North Carolina 2016, ISBN 978-0-7864-9404-0 (google.com).

- Kristien Geenen: Categorizing colonial patients: Segregated medical care, space and decolonization in a Congolese city, 1931–62. In: The Journal of the International African Institute. 89. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2019, ISSN 1750-0184, S. 100–124, doi:10.1017/S0001972018000724.

- Jules Gérard-Libois (Hrsg.): Congo 1959. Centre de Recherche et d'Information Sociopolitiques, Brussels 1960, OCLC 891524823 (issuu.com).

- Rosalyn Higgins (Hrsg.): Africa (= United Nations Peacekeeping, 1946–1967: Documents and Commentary. Band 3). Oxford University Press, Oxford 1980, ISBN 978-0-19-218321-7 (google.com).

- Catherine Hoskyns: The Congo Since Independence: January 1960 – December 1961. Oxford University Press, London 1965, OCLC 414961.

- Adam M. Howard (Hrsg.): Congo, 1960–1968 (= Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968. Band XXIII). United States Department of State, Washington, D.C. 2013, OCLC 11040892 (state.gov [PDF]).

- J. M. Jadot: Les écrivains africains du Congo belge et du Ruanda-Urundi. Académie Royale des Sciences Coloniales, Brussels 1959, OCLC 920174792 (französisch, kaowarsom.be [PDF]).

- Thomas R. Kanza: The Rise and Fall of Patrice Lumumba: Conflict in the Congo. expanded Auflage. Schenkman Books, Inc., Rochester, Vermont 1994, ISBN 978-0-87073-901-9.

- Michael Kasongo: History of the Methodist Church in the Central Congo. University Press of America, New York 1998, ISBN 978-0-7618-0882-4 (google.com).

- John Kent: America, the UN and Decolonisation: Cold War Conflict in the Congo. Routledge, London 2010, ISBN 978-1-136-97289-8 (google.com).

- Colin Legum: Congo Disaster. Penguin, Harmondsworth 1961, OCLC 250351449 (archive.org).

- René Lemarchand: Political Awakening in the Belgian Congo. University of California Press, Berkeley 1964, OCLC 654220190 (google.com).

- Alan P. Merriam: Congo: Background of Conflict. Northwestern University Press, Evanston 1961, OCLC 732880357 (archive.org).

- Mabi Mulumba, Mutamba Makombo: Cadres et dirigeants au Zaïre, qui sont-ils?: dictionnaire biographique. Editions du Centre de recherches pédagogiques, Kinshasa 1986, OCLC 462124213 (französisch, google.com).

- Okwudiba Nnoli: Government and politics in Africa: a reader. AAPS Books, Mount Pleasant, Harare 2000, ISBN 978-0-7974-2127-1 (google.com).

- Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja: Class Struggles and National Liberation in Africa: Essays on the Political Economy of Neocolonialism. Omenana, Roxbury, Boston 1982, ISBN 978-0-943324-00-5 (google.com).

- Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja: Patrice Lumumba. illustrated, reprint Auflage. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 2014, ISBN 978-0-8214-4506-8 (google.com).

- Conor Cruise O'Brien: To Katanga And Back - A UN Case History. Hutchinson, London 1962, OCLC 460615937 (archive.org).

- Victor Promontorio: Les institutions dans la constitutions congolaise. Concordia, Léopoldville 1965, OCLC 10651084 (französisch, google.com).

- Michael G. Schatzberg: The Dialectics of Oppression in Zaire. illustrated, reprint Auflage. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1991, ISBN 978-0-253-20694-7 (google.com).

- Ronald Segal: Africa South. reprint Auflage. Band 4. Africa South Publications, Cape Town 1971 (google.com).

- Jean Omasombo Tshonda (Hrsg.): Mongala: Jonction des territoires et bastion d'une identité supra-ethnique (= Provinces). Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren 2015, ISBN 978-94-92244-16-1 (französisch, africamuseum.be [PDF]).

- Jean Omasombo Tshonda, Benoît Verhaegen: Patrice Lumumba: acteur politique: de la prison aux portes du pouvoir, juillet 1956-février 1960. Harmattan, 2005, ISBN 978-2-7475-6392-5 (französisch, google.com).

- Jean-Claude Willame: Patrimonialism and Political Change in the Congo. Stanford University Press, Stanford 1972, ISBN 978-0-8047-0793-0 (archive.org).

- Ludo De Witte: The Assassination of Lumumba. illustrated Auflage. Verso, London 2002, ISBN 978-1-85984-410-6 (google.com).

- Crawford Young: Politics in Congo: Decolonization and Independence. reprint Auflage. Princeton University Press, Princeton 2015, ISBN 978-1-4008-7857-4 (google.com).

- Crawford Young, Thomas Edwin Turner: The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State. reprint Auflage. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin 2013, ISBN 978-0-299-10113-8 (google.com).

Einzelnachweise

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Dieumerci Monga Monduka: In mémoriam: Jean Bolikango: 25 ans déjà. In: Digital Congo. Multimedia Congo s.p.r.l., 22. Februar 2007, archiviert vom am 1. Dezember 2009; abgerufen am 27. November 2016 (französisch).

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ a b c d e Vorlage:Cite magazine

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ a b Jean-Chrétien Ekambo: La Voix du Congolais s'est éteinte. 21. Februar 2010, abgerufen am 28. September 2018 (französisch).

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ Keith Kyle: Congo: The First Nation of Africa? 9. April 1964, S. 6, abgerufen am 29. Juli 2017.

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ .

- ↑ 30 juin 2016: la RDC célèbre son 56e anniversaire d'indépendance sur fond d'impasse politique. Radio Okapi, 30. Juni 2016, abgerufen am 20. Februar 2017 (französisch).

- ↑ Congo Celebrates 50th Anniversary of Independence. In: Congo Planet. Congo News Agency, 30. Juni 2010, abgerufen am 20. Februar 2010.

- ↑ Le Chef de l'Etat décerne ŕ titre posthume une médaille du mérite civique ŕ Jean Bolikango. In: Digital Congo. Multimedia Congo s.p.r.l., 7. März 2005, archiviert vom am 25. Oktober 2017; abgerufen am 27. März 2017 (französisch).

- ↑ .

<nowiki> Kategorie:Geboren 1909 Kategorie:Gestorben 1982

| Personendaten | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Bolikango, Jean |

| KURZBESCHREIBUNG | Kongolesischer Lehrer, Journalist und Politiker |

| GEBURTSDATUM | 1909 |

| STERBEDATUM | 1982 |

Popular Movement of the Revolution politicians]]

Kategorie:People of the Congo Crisis Kategorie:Deputy Prime Ministers of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Kategorie:Candidates for President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Kategorie:Belgian Congo people Kategorie:People from Kinshasa Kategorie:Democratic Republic of the Congo writers Kategorie:Democratic Republic of the Congo male writers Kategorie:Royal Order of the Lion recipients Kategorie:Democratic Republic of the Congo pan-Africanists Kategorie:Recipients of the Benemerenti medal