Benutzer:Hajo-Muc/Syrien (historische Landschaft)

Syrien oder arabisch Scham (ٱلشَّام aš-Šām) ist der Name einer zumeist in historischem Kontext verwendeten Region im Osten des Mittelmeers. Sie liegt im Nahen Osten. Gelegentlich wird auch der ebenfalls meist in historischen Kontext verwendete Begriff Levante auf diese Region bezogen.[A 1] Im modernen Sprachgebrauch (seit dem Ende des Ersten, noch mehr seit dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs) beschränkt sich der Gebrauch des Begriffs Syrien im Wesentlichen auf das Gebiet der Arabischen Republik Syrien, deren Gebiete östlich des Euphrat historisch nicht immer zu Syrien gerechnet wurden. Unmittelbar nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, vor der definitiven Verteilung der der vormaligen osmanischen Provinzen auf die europäischen Mandatsmächte Großbritannien und Frankreich war das Territorium auch als Groß-Syrien bekannt.

Politisch war Syrien in historischer Zeit oft in kleinere Staaten, oft Stadtstaaten aufgeteilt, die meist nicht den Namen Syrien führten. Lediglich das aramäische Königreich Damaskus aus dem alten Testament wird auch als Syrien bezeichnet. Soweit Syrien Bestandteil größerer Reiche, wie des Römischen oder Osmanischen Reiches war, wurden Verwaltungsbezirke mit diesem Namen bezeichnet, die meist nicht den gesamten geographischen Raum von Syrien bzw. al-Scham einnahmen. Bei den beiden historischen Großreichsbildungen, die ihr Zentrum in der Region Syrien hatten, dem Seleukidenreich und dem Omayyaden-Kalifat werden nur die seleukidischen Könige auch als „Könige von Syrien“ bezeichnet. Aus diesen Gründen ist oft nur aus dem Kontext zu erschließen, welches geographische Gebiet mit der Bezeichnung Syrien tatsächlich gemeint ist.

Etymologie und Begriffsgeschichte

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Etymologie

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Syrien

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]asch-Scham

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Greater Syria has been widely known as Ash-Shām. The term etymologically in Arabic means "the left-hand side" or "the north", as someone in the Hejaz facing east, oriented to the sunrise, will find the north to the left.

The Shaam region is sometimes defined as the area that was dominated by Damascus, long an important regional center. In fact, the word Ash-Sām, on its own, can refer to the city of Damascus.[1] Continuing with the similar contrasting theme, Damascus was the commercial destination and representative of the region in the same way Sanaa held for the south.

Die Bezeichnungen „Syrer“ und „syrisch“

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Umfasstes Gebiet und Grenzen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

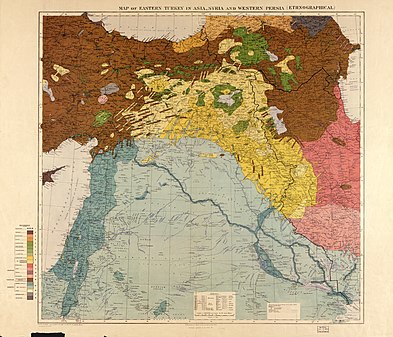

„Syrien“ im geographischen Sinn, wie der name besonders vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg gebraucht wurde, bezog sich auf ein Gebiet im Nahen Osten, daim Westen von Mittelmeer und ab der Nordostspitze des Golfs von Iskenderun vom Amanusgebirge, Im Norden durch den Taurus, im Osten durch den Euphrat und die Syrische Wüste und im Süden durch die Sinai-Halbinsel begrent wird, Gelegentlich, dann auch unter der Bezeichnung Großsyrien, wurden auch trans-euphratische Gebiete bis zum Habur einbezogen. refers to the entire northern Levante, including İskenderun and the Ancient City of Antakya or in an extended sense the entire Levant as far south as Ägypten, but not including Mesopotamien. The area of "Greater Syria" ({{lang|ar|سُوْرِيَّة ٱلْكُبْرَىٰ|link=no}}, ''{{transliteration|ar|Sūrīyah al-Kubrā}}''); also called "Natural Syria" ({{lang|ar|سُوْرِيَّة ٱلطَّبِيْعِيَّة|link=no}}, ''{{transliteration|ar|Sūrīyah aṭ-Ṭabīʿīyah}}'') or "Northern Land" ({{lang|ar|بِلَاد ٱلشَّام|link=no}}, ''{{transliteration|ar|Bilād ash-Shām}}''),[2] extends roughly over the Bilad al-Sham province of the medieval Arab caliphates, encompassing the Eastern Mediterranean (or Levant) and Western Mesopotamia. The Muslim conquest of the Levant in the seventh century gave rise to this province, which encompassed much of the region of Syria, and came to largely overlap with this concept. Other sources indicate that the term Greater Syria was coined during osmanischen Herrschaft, after 1516, to designate the approximate area included in present-day Palestine, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel.[3]

Die Unsicherheit der Definition der Ausdehnung von „Syrien“ wird verstärkt durch die Konfusion der Namen Syrien and Assyrien. The question of the ultimate etymological identity of the two names remains open today, but regardless of etymology, the two names have often been taken as exchangeable or synonymous from the time of Herodotus.[4] However, in the Roman Empire, 'Syria' and 'Assyria' began to refer to two separate entities, Roman Syria and Roman Assyria.

Today, the largest metropolitan areas in the region are Amman, Tel Aviv, Damascus, Beirut, Aleppo and Gaza City.

Geschichte

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Altorientalisches Syrien

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Herodot benutzt den Namen Syrien (altgriechisch Συρία Syria) mit unterschiedlichen Bedeutungen. to refer to the stretch of land from the Halys river, including Kappadokien (Historien, I.6) in today's Turkey to the Mount Casius (Historien II.158), which Herodotus says is located just south of Lake Serbonis (The Histories III.5). According to Herodotus various remarks in different locations, he describes Syria to include the entire stretch of Phoenician coastal line as well as cities such Cadytis (Jerusalem) (Historien II.159).[4]

Hellenistisches Syrien

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]In Greek usage, Syria and Assyria were used almost interchangeably, but in the Roman Empire, Syria and Assyria came to be used as distinct geographical terms. "Syria" in the Roman Empire period referred to "those parts of the Empire situated between Asia Minor and Egypt", i.e. the western Levant, while "Assyria" was part of the Persian Empire, and only very briefly came under Roman control (116–118 AD, marking the historical peak of Roman expansion).

Römisches Syrien

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

In the Roman era, the term Syria is used to comprise the entire northern Levant and has an uncertain border to the northeast that Plinius der Ältere describes as including, from west to east, the Kingdom of Kommagene, Sophene, and Adiabene, "formerly known as Assyria".[5]

Various writers used the term to describe the entire Levant region during this period; the New Testament used the name in this sense on numerous occasions.[6]

In 64 BC, Syria became a province of the Roman Empire, following the conquest by Pompeius Magnus. Roman Syria bordered Judäa to the south, Anatolian Greek domains to the north, Phoenicia to the West, and was in constant struggle with Parthians to the East. In 135 AD, Syria-Palaestina became to incorporate the entire Levant and Western Mesopotamia. In 193, the province was divided into Syria Coele (Koilesyrien) and Syria Phoenice. Sometime between 330 and 350 (likely c. 341), the province of Euphratensis was created out of the territory of Syria Coele and the former realm of Commagene, with Hierapolis as its capital.[7]

After c. 415 Syria Coele was further subdivided into Syria I, with the capital remaining at Antiochia, and Syria II or Salutaris, with capital at Apamea am Orontes. In 528, Justinian I. carved out the small coastal province Theodorias out of territory from both provinces.[8]

Bilad asch-Scham

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Die Region kam unter die Herrschaft des Kalifats nach dem muslimischen Sieg über das Oströmische Reich in der Schlacht am Jarmuk und wurde bekannt als Bilad asch-Scham. Während des Umayyaden-Kalifats wurde Schām in fünf Dschunds oder Militärbezirke aufgeteilt. Dies waren Dschund Dimashq (für das Gebiet von Damaskus), Dschund Ḥimṣ (für das Gebiet von Homs), Dschund Filasṭīn (für das Gebiet von Palästina) and Jund al-Urdunn (für das Gebiet von Jordanien). Später wurde noch der Dschund Qinnasrîn vom Dschund Hims abgeteilt. Damaskus war die Hauptstadt des Kalifats bis zum Beginn der Herrschaft der Abbassiden.[9][10][11]

Die spätere Geschichte Syriens ist durch das Eingreifen auswärtiger Mächte und innerer Zersplitterung geprägt. Im 9. Jahrhundert wurden die Hamdaniden zur Vormacht in NordsyrienVon Süden, von Ägypten her, drängten die Tuluniden, die Ichschididen und schließlich die Fatimiden, die schiitischen Kalifen von Kairo in das Land. Von Norden her begann im 9. Jahrhundert die soganannte byzantinische Reconquista, auf deren Gipfel die Kaiser Nikephoros Phokas, Johannes Tzimiskes und Basileios II. zeitweise bis nach Palästina vorrücken konnten. Antiochia, aber auch vorübergehend Damaskus, Akko und Caesarea in Palaestina fielen in byzantinische Hand. Im Osten gewannen die Byzantiner Edessa zurück, die Hamdaniden von Aleppo mussten sich unterwerfen. Die Eroberungen im Süden mussten allerdings aufgegeben werden.

Das Eingreifen der Seldschuken im 11. Jahrhundert änderte die Lage. Die Byzantiner verloren Stück für Stück ihre Eroberungen in Syrien wieder, insbesondere in den Jahrzehnten, die auf die Niederlage in der Schlacht bei Manzikert folgten. Als nach dem Tod des Seldschukenherrschers Malik Schah I. das Reich der Seldschuken zerfiel, führten die nunmehr ungezügelten Angriffe ihrer türkischen Gefolgsleute zum Hilferuf des byzantinischen Kaisers Alexios Komnenos an den Papst Urban II., der zum Ersten Kreuzzug führte. In der Folge entstanden die Kreuzfahrerstaaten (Grafschaft Edessa, Fürstentum Antiochia, Grafschaft Tripolis und Königreich Jerusalem), denen die muslimischen Staaten Mossul, Aleppo und Damaskus gegenüberstanden. Den Zengiden, einer türkischen Dynastie in Mossul gelang es schließlich, die muslimischen Staaten Syrien unter ihre Kontrolle zu bringen und mit der Grafschaft Edessa den ersten und exponiertesten Kreuzfahrerstaat zu liquidieren. Nur ad-Din entsandte ein Heer nach Ägypten. Dessen Führer Saladin machte sich zum Herrn des Landes, beseitigte die Nachfolger Nur ad-Dins in Syrien und trat deren Nachfolge an. Ihm gelang die Zerschlagung des Königreichs Jerusalen in der Schlacht an den Hörnern von Hattin 1187 und die Rückeroberung von Jerusalem. Er begründete die Dynastie der Ayyubiden, die in der Folge über Ägypten, Syrien, Obermesopotamien und Westarabien herrschte, währen an der Mittelmeerküste die Reste der Kreuzfahrerstaaten fortbestanden.

Das Erscheinen der Mongolen änderte erneut die Lage. An die Stelle der Ayyubiden traten ihre Militärsklaven, die Mamluken, denen es gelang, den Siegeszug der Mongolen in der Schlacht an der Goliathsquelle 1250 aufzuhalten und dauerhaft die Herrschaft des mongolischen Il-Khanats auf die Gebiete östlich des Euphrats und nördlich des Taurus zu begrenzen. Sie bereiteten auch bis 1291 die letzten Stützpunkte der Kreuzfahrer an der syrischen Küste. Zu Beginn des 16. Jahrhundert erschienen die Osmanen als Eroberer in Syrien. Nachdem Sultan Selim I. die Safawiden geschlagen hatte, die die Nachfolge der Ilkhane und ihrer weiteren Nachfolger, der Timuriden und der Qara Qoyunlu und Aq Qoyunlu angetreten hatten in der Schlacht bei Tschaldiran 1514 vernichtend geschlagen hatte, eroberte er in den folgenden Jahren das Mamelukenreich und verleibte somit Syrien dem Osmanischen Reich ein. Seine Nachfolger drängten auch das persische Safawidenreich zurück, bis schließlich die Westgrenze der das Hochland von Iran beherrschenden Reiche, die seit der Antike meist an der Euphratlinie gelegen hatte, dauerhaft auf die heutige türkisch-irakisch-iranische Grenze zurückverlegt wurde. Das Land war in mehrere Provinzen eigeteilt, darunter die Provinz von Scham mit der Hauptstadt Damaskus, die deren Namen übernahm und noch heute im Türkischen Şam heißt.

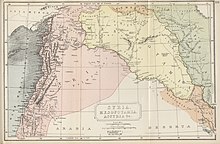

Spätosmanisches Syrien

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]In the later ages of the Ottoman times, it was divided into wilayahs or sub-provinces the borders of which and the choice of cities as seats of government within them varied over time. The vilayets or sub-provinces of Aleppo, Damascus, and Beirut, in addition to the two special districts of Mount Lebanon and Jerusalem. Aleppo consisted of northern modern-day Syria plus parts of southern Turkey, Damascus covered southern Syria and modern-day Jordan, Beirut covered Lebanon and the Syrian coast from the port-city of Latakia southward to the Galilee, while Jerusalem consisted of the land south of the Galilee and west of the Jordan River and the Wadi Arabah.

Although the region's population was dominated by Sunni Muslims, it also contained sizable populations of Shi'ite, Alawite and Ismaili Muslims, Syriac Orthodox, Maronite, Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholics and Melkite Christians, Jews and Druze.

Faisals Königreich Syrien und die französische Okkupation

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]<-- -->

The Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (OETA) was a British, French and Arab military administration over areas of the former Ottoman Empire between 1917 and 1920, during and following World War I. The wave of Arab nationalism evolved towards the creation of the first modern Arab state to come into existence, the Hashemite Arab Kingdom of Syria on 8 March 1920. The kingdom claimed the entire region of Syria whilst exercising control over only the inland region known as OETA East. This led to the acceleration of the declaration of the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon and British Mandate for Palestine at the 19–26 April 1920 San Remo conference, and subsequently the Franco-Syrian War, in July 1920, in which French armies defeated the newly proclaimed kingdom and captured Damascus, aborting the Arab state.[12]

Thereafter, the French general Henri Gouraud, in breach of the conditions of the mandate, subdivided the French Mandate of Syria into six states. They were the states of Damascus (1920), Aleppo (1920), Alawite State (1920), Jabal Druze (1921), the autonomous Sanjak of Alexandretta (1921) (modern-day Hatay in Turkey), and Greater Lebanon (1920) which later became the modern country of Lebanon.

Pan-Syrischer Nationalismus

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The boundaries of the region have changed throughout history, and were last defined in modern times by the proclamation of the short-lived Arab Kingdom of Syria and subsequent definition by French and British mandatory agreement. The area was passed to French and British Mandates following World War I and divided into Greater Lebanon, various Syrian-mandate states, Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan. The Syrian-mandate states were gradually unified as the State of Syria and finally became the independent Syria in 1946. Throughout this period, Antoun Saadeh and his party, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, envisioned "Greater Syria" or "Natural Syria", based on the etymological connection between the name "Syria" and "Assyria", as encompassing the Sinai Peninsula, Cyprus, modern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, the Ahvaz region of Iran, and the Kilikian region of Turkey.[13][14]

Religious significance

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The region has sites that are significant to Abrahamic religions:[2][15][16]

-->

Anmerkungen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ M. L. Steiner und Ann E. Killebrew (Hrsg.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant. C. 8000 - 332 BCE. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-921297-2, Introduction, S. 2: „The western coastline and the eastern deserts set the boundaries for the Levant ... The Euphrates and the area around Jebel el-Bishrī mark the eastern boundary of the northern Levant, as does the Syrian Desert beyond the Anti-Lebanon range's eastern hinterland and Mount Hermon. This boundary continues south in the form of the highlands and eastern desert regions of Transjordan.“ [https://books.google.com/books?id=5H4fAgAAQBAJ&pg=PT25 bei Google-Books

Einzelnachweise

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ Tardif, P.: 'I won't give up': Syrian woman creates doll to help kids raised in conflict, CBC News, 17 September 2017. Abgerufen im 6 March 2018

- ↑ a b Mustafa Abu Sway: The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source ( des vom 28 July 2011 im Internet Archive), Central Conference of American Rabbis

- ↑ Thomas Collelo, ed. Lebanon: A Country Study Washington, Library of Congress, 1987.

- ↑ a b Herodotus: Herodotus VII.63. Fordham University (englisch): „VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.“

- ↑ Plinius der Ältere: Natural History. University of Chicago, 1998, ISBN 84-249-1901-7, Book 5 Section 66 (englisch, uchicago.edu).

- ↑ A commentary on the Bible, quote "In the time of the Greek predominance it came into use. as it is employed to-day, as the name of the whole western borderland of the Mediterranean, and in the NT it is used several times in that sense (Mt. 4:24, Lk. 2:2, Ac. 15:23,41, 18:18, 21:3, Gal. 1:21)".

- ↑ Alexander Kazhdan (Hrsg.): [[Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium]]. Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, S. 748 (englisch).

- ↑ Alexander Kazhdan (Hrsg.): [[Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium]]. Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, S. 1999 (englisch).

- ↑ Guy Le Strange: Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, London 1890, S. 30-234 Online

- ↑ Khalid Yahya Blankinship: The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads, SUNY, Albany 1994, 47-50 (Vorschau auf Google Books)

- ↑ Paul M. Cobb: White Banners: Contention in 'Abbāsid Syria, 750–880. SUNY, Albany 2001, ISBN 0-7914-4880-0, S. 12–182 (Vorschau auf Google Books)

- ↑ Itamar Rabinovich, Symposium: The Greater-Syria Plan and the Palestine Problem in The Jerusalem Cathedra (1982), p. 262.

- ↑ Antoun Sa'adeh: The Genesis of Nations. Beirut 2004 (englisch). Translated and Reprinted

- ↑ Ehud Ya'ari: Behind the Terror. In: The Atlantic. Juni 1987 (englisch).

- ↑ World Heritage Committee: Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. 2. Juli 2007, S. 34, abgerufen am 8. Juli 2008 (englisch).

- ↑ J. M. O'Connor: The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-19-152867-5, S. 369 (englisch, google.com).

{{Palestine (historical region) topics}} {{Israel topics}} {{Jordan topics}} {{Lebanon topics}} {{Palestine topics}} {{Syria topics}} {{Regions of Turkey}} [[Category:Syria (region)| ]] [[Category:Levant]] [[Category:Near East]] [[Category:Ancient Near East]] [[Category:Geography of Syria]] [[Category:Geography of Jordan]] [[Category:Geography of the Middle East]] [[Category:Geography of Western Asia]] [[Category:Geographic history of Syria]] [[Category:History of Cyprus]] [[Category:History of Israel]] [[Category:History of Palestine (region)]] [[Category:History of Lebanon]] [[Category:History of Jordan]] [[Category:History of Turkey]] [[Category:History of Adana Province]] [[Category:History of Kahramanmaraş Province]] [[Category:History of Gaziantep Province]] [[Category:History of Mersin Province]] [[Category:History of Hatay Province]] [[Category:History of the Levant]] [[Category:Historical regions]] [[Category:Irredentism|Syria]] [[Category:Nationalist movements in Asia|Syria]] [[Category:Politics of Syria]] [[Category:Political movements]] [[Category:Regions of Asia]] [[Category:Syrian nationalism]] [[Category:Sykes–Picot Agreement| Consequences]] [[Category:1910s in Mandatory Syria]] [[Category:1920s in Mandatory Syria]]