Kadma we-asla

| Betonungszeichen oder Akzent Unicodeblock Hebräisch | |

|---|---|

| Zeichen | ֨ ֜ |

| Unicode | U+05A8 U+059C |

| Kadma we-Azla (aschkenasisch) | קַדְמָ֨א וְאַזְלָ֜א |

| Azla Gerisch[1][2] (sephardisch) | אַזְלָ֨א גְּרִ֜ישׁ |

| Kadma-Geresch[3][4] (italienisch) | קַדְמָ֨א-גֵּ֜רֵשׁ |

| Aslo-Tares (jemenitisch) | אַזְלָ֨א טָרֵ֜ס |

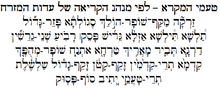

Kadma we-asla[5][6] ֨ ֜ (aramäisch: קַדְמָ֨א וְאַזְלָ֜א[5][7]) ist eine Trope (von jiddisch טראָפּ trop[8]) in der jüdischen Liturgie und zählt zu den biblischen Satz-, Betonungs- und Kantillationszeichen Teamim, die im Tanach erscheinen.[9]

Beschreibung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

In der aschkenasischen Tradition wird die Trope Kadma we-Asla, Qadma we-Azla oder Kadma Azla[10] (aramäisch: קַדְמָ֨א וְאַזְלָ֜א) genannt.[11] In der Jerusalemer bzw. sephardischen Tradition wird sie Azla gerisch (aramäisch: אַזְלָ֨א גְּרִ֜ישׁ)[1][2] genannt. In der italienischen Tradition wird sie auch Kadma-Geresch (aramäisch: קַדְמָ֨א גֵּ֜רֵשׁ) genannt.[4] Jacobson erwähnt, dass andere Literatur diese Form der Betonung Kadmah azla nennen, er zieht jedoch die Bezeichnung Kadmah geresch vor:

“Since, strictly speaking, only word accented on the next-to-the-last-syllable can be marked with geresh, some books refer to this combination as kadmah azla when the second word is accented on the last syllable. In this book, we do not use the term azla.”

In der jemenitischen Tradition wird sie auch „Aslo tares“ genannt.[12]

Erscheinen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Kadma we-Asla geht folgenden Zeichen voraus: Mahpach, Tewir und Rewia. Ein Kadma kann auch ohne Asla (Geresch) vor einem Mahpach gefunden werden, und ein Asla (Geresch) ohne Kadma. Dann wird dieses als „Azla-geresh“ oder einfach als Geresch bezeichnet. Kadma-we-Asla wird oft durch Gerschajim ersetzt, der die gleichen Aufgaben wie Kadma-we-Asla erfüllt. Gerschajim geht auch – so wie Kadma-we-Asla – folgende Zeichen voraus: Mahpach, Tewir und Rewia.

Kadma-we-Asla

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Es entsteht wenn ein Wort das Betonungszeichen Geresch (bzw. Asla) trägt. Wenn sich zusätzlich ein anderes vorhergehendes Wort auf dieses bezieht, dann wird der Vorgänger mit dem konjunktiven Betonungszeichen Kadma ausgestattet. Das so entstandene Wörterpaar wird nach diesen Betonungszeichen entweder Kadma-Geresch oder Kadma-Asla genannt.[13] Kadma-we-Asla erscheint 1733 mal in der Tora.[14] Die Symbole von Kadma-we-Asla ähneln laut Rosenberg den gekrümmten Fingern zweier ausgestreckter Hände.[15][16] Jacobson illustriert dies am Beispiel Numeri 7,11 BHS (נָשִׂ֨יא אֶחָ֜ד).[17] Zudem erscheint Kadma-we-Asla in Numeri 35,5 BHS (וְאֶת־פְּאַת־נֶגֶב֩ אַלְפַּ֨יִם בָּאַמָּ֜ה).

Kadma-we-Asla und Telischa Ketanna

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Wenn sich zusätzlich ein anderes vorhergehendes Wort auf das Paar Kadma-we-Asla[16] bezieht, dann wird der Vorgänger mit dem konjunktiven Betonungszeichen Telischa Ketanna ausgestattet.

Jacobson illustriert dies an den Beispielen Exodus 38,1 BHS (חָמֵשׁ֩ אַמֹּ֨ות אָרְכֹּ֜ו), Numeri 20,6 BHS (וַיָּבֹא֩ מֹשֶׁ֨ה וְאַהֲרֹ֜ן), Levitikus 11,42 BHS (כֹּל֩ הֹולֵ֨ךְ עַל־גָּחֹ֜ון), Deuteronomium 28,69 BHS (אֵלֶּה֩ דִבְרֵ֨י הַבְּרִ֜ית), Genesis 19,30 BHS (וַיַּעַל֩ לֹ֨וט מִצֹּ֜ועַר).

Kadma-we-Asla und Telischa Ketanna und Munach

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Wenn noch ein weiteres vorhergehendes Wort folgt, das sich auf Kadma-we-Asla bezieht, wird das Betonungszeichen Munach verwendet.[18]

Jacobson illustriert dies an den Beispielen Genesis 50,13 BHS (אֲשֶׁ֣ר קָנָה֩ אַבְרָהָ֨ם אֶת־הַשָּׂדֶ֜ה), Genesis 12,5 BHS (וַיִּקַּ֣ח אַבְרָם֩ אֶת־שָׂרַ֨י אִשְׁתֹּ֜ו), Exodus 15,19 BHS (כִּ֣י בָא֩ ס֨וּס פַּרְעֹ֜ה), Exodus 27,18 BHS (אֹ֣רֶךְ הֶֽחָצֵר֩ מֵאָ֨ה בָֽאַמָּ֜ה), Genesis 38,11 BHS (וַיֹּ֣אמֶר יְהוּדָה֩ לְתָמָ֨ר כַּלָּתֹ֜ו).

Melodien

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Laut der The Jewish Encyclopedia 1901–1906 Band III beschreibt Francis Lyon Cohen (1862–1934) – Autor von The Handbook of Synagogue Music (1889) und Song in the Synagogue in The Musical Times (London, 1899) – zahlreiche individuelle Melodien für Kadma-we-Asla:[5]

- Pentateuch: aschkenasisch, sephardisch, aus Marokko, Ägypten und Syrien sowie aus Bagdad.

- Propheten und Haftara: aschkenasisch, sephardisch sowie aus Bagdad.

- Esther: aschkenasisch, sephardisch.

- Klagelieder: aschkensiasch, sephardisch sowie aus Marokko, Ägypten und Syrien.

- Ruth: sephardisch

Konkordanzen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]| Buch | Kadma we-Asla ֨ ֜ |

|---|---|

| Torah | 1733[14] |

| בְּרֵאשִׁית Bereschit | 427[14] |

| שִׁמוֹת Schemot | 373[14] |

| וַיִּקְרׇא Wajikra | 307[14] |

| בְּמִדְבַּר Bemidbar | 393[14] |

| דְּבָרִים Dewarim | 413[14] |

| נְבִיאִים Newi'im | 1492[19] |

| כְּתוּבִים Ketuwim | 1240[19] |

Literatur

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- William Wickes: A treatise on the accentuation of the three so-called poetical books on the Old Testament, Psalms, Proverbs, and Job. 1881 (archive.org).

- William Wickes: A treatise on the accentuation of the twenty-one so-called prose books of the Old Testament. 1887 (archive.org).

- Arthur Davis: The Hebrew accents of the twenty-one Books of the Bible (K"A Sefarim) with a new introduction. 1900 (archive.org).

- Francis L. Cohen: Cantillation. In: Isidore Singer (Hrsg.): The Jewish Encyclopedia. Band III. KTAV Publishing House, New York 1902, S. 542–548 (englisch, de.scribd.com).

- Solomon Rosowsky: The Cantillation of the Bible. The Five Books of Moses. The Reconstructionist Press, New York 1957 (englisch).

- James D. Price: Concordance of the Hebrew accents in the Hebrew Bible. Band I: Concordance of the Hebrew Accents used in the Pentateuch. Edwin Mellon Press, Lewiston NY 1996, ISBN 0-7734-2395-8 (englisch, eingeschränkte Vorschau in der Google-Buchsuche).

- Joshua R. Jacobson: Chanting the Hebrew Bible. The art of cantillation. 1. Auflage. Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia 2002, ISBN 0-8276-0693-1 (englisch).

- Joshua R. Jacobson: Chanting the Hebrew Bible. Student Edition. The Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 0-8276-0816-0 (englisch, eingeschränkte Vorschau in der Google-Buchsuche).

Weblinks

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- zusammenhängende und einheitliche Melodie zu Kadma-w'Asla auf youtube.com

- zusammenhängende und einheitliche Melodie zu Kadma-w'Asla auf Torah Trope Exercises

- zusammenhängende und einheitliche Melodie zu Kadma-w'Asla auf youtube.com

- Listen to Kadma-V’azla and Telisha-Gedola here. auf mwjdstefillah.wordpress.com

Einzelnachweise

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ a b »Le deuxième Ish E’had est sous le signe de Azla Guérish, אַזְלָ֨א גְּרִ֜ישׁ, il représente cette fois, Kalev, car Kalev, la première chose qu’il alla faire en arrivant en Israel c’est de prier sur la tombe des patriarches, c’est le sens de « Azla – il alla » « Guérish – Guimel Resh » les trois têtes, ce sont les trois patriarches, la tête et le début du peuple d’Israel. Azla Guérish veut donc dire aller pèleriner les Avot, et c’est ce que ce deuxième Ish E’had veut représenter, Kalev Ben Yéfouné. (על פי עוד יוסף חי דרשות – פרשת שלח לך)« aus Nishmat-Haim. Quelques perles de Torah en direct de Yeroushalaim

- ↑ a b (hebräisch אזלא גריש oder אַזְלָ֨א גְּרִ֜ישׁ) Asla-Gerisch auf YouTube.com

- ↑ Jacobson (2005), S. 68.

- ↑ a b קדמא-גרש tanach parshanut taamey auf www.daat.ac.il

- ↑ a b c Francis L. Cohen: Cantillation. In: Isidore Singer (Hrsg.): The Jewish Encyclopedia. Band III, KTAV Publishing House, New York 1901–1906, S. 544: Kad-ma we-az-la, Preceding and Going on. (Textarchiv – Internet Archive).

- ↑ Melodie zu Kadma-w'Asla auf youtube.com

- ↑ Joshua R. Jacobson: Chanting the Hebrew Bible. The art of cantillation. Jewish Publication Society. Philadelphia 2002. ISBN 0-8276-0693-1, S. 407, 936.

- ↑ Jacobson (2002), S. 3: Trop. «In Yiddish, the lingua franca of the Jews in Northern Europe […], these accents came to bei known as trop. The derivation of this word seems to be from the Greek tropos or Latin tropus ».

- ↑ Solomon Rosowsky: The Cantillation of the Bible. The Five Books of Moses. The Reconstructionist Press, New York 1957 (englisch): “Cantillation proceeds according to the special graphic signs–tropes or accents–attached to every word in the Bible.“ in Verbindung mit einer Fußnote zu tropes: „In this work we use the term trope (Greek tropos – turn) long accepted in Jewish practice.”

- ↑ Jacobson (2005), S. 68.

- ↑

פרשה בפני עצמה הם השמות 'קדמא ואזלא' 'אזלא גרש' הנהוגים אצל האשכנזים: הטעם המפסיק הנקרא גֵּרֵשׁ או גְּרִישׁ או טרס, נקרא אצל האשכנזים 'אזלא' במקרה שיש לפניו את הטעם המשרת הנקרא 'קדמא'. אבל אם הוא מופיע לבד, הוא נקרא 'אזלא גרש'. מדוע שני השמות? ומדוע אותו טעם נקרא 'אזלא' כשהוא מופיע עם קדמא לפניו, ו'אזלא גרש' כשהוא מופיע בלי קדמא?

– Uriel Frank - ↑ נוסח תימן Jemenit. Tradition auf YouTube.com

- ↑ Sofern nicht anders ausgewiesen, folgt dieser Abschnitt dem Kapitel Two Words in a (Single) Geresh Segment in Jacobson (2005), S. 68.

- ↑ a b c d e f g James D. Price: Concordance of the Hebrew accents in the Hebrew Bible: Concordance … 1. Band. S. 6.

- ↑ Rosenberg, S. 129.

- ↑ a b Sofern nicht anders ausgewiesen, folgt dieser Abschnitt den Kapiteln Two Words in the (Single) Geresh Segment und Three Words in the (Single) Geresh Segment in Jacobson (2005), S. 68 f.

- ↑ Jacobson (2005), S. 68.

- ↑ Sofern nicht anders ausgewiesen, folgt dieser Abschnitt dem Kapitel Four Words in the (Single) Geresh Segment in Jacobson (2005), S. 69.

- ↑ a b James D. Price: Concordance of the Hebrew accents in the Hebrew Bible: Concordance … 1. Band. S. 5.